Told by the Dead by Ramsey Campbell, containing the following stories: "Return Journey" (2000) "Twice by Fire" (1998) "Agatha's Ghost" (1999) "Little Ones" (1999) "The Last Hand" (1975) "Facing It" (1995) "Never to be Heard" (1998) "The Previous Tenant" (1975) "Becoming Visible" (1999) "No End of Fun" (2002) "After the Queen" (1977) "Tatters" (2001) "Accident Zone" (1995) "The Entertainment" (1999) "Dead Letters" (1978) "All for Sale" (2001) "No Strings" (2000) "The Worst Fog of the Year" (1990) "The Retrospective" (2002) "Slow" (1985) "Worse than Bones" (2001) "No Story In It" (2000) and "The Word" (1997) (2003):

I think this may be Campbell's best first-time-reprinted collection in his now-50-years-and-counting career. It's a bit of a retrospective, as the stories were written between 1968 and 2001 but weren't collected in any of his other collections. There's a story in here called "The Retrospective." Oh ho!

Campbell's writerly voice (as Poppy Z. Brite notes in her generous introduction) has remained strangely constant even as his prose has richened and deepened -- a 1968 Campbell story is recognizably by him, the early emulation of H.P. Lovecraft's prose style already pretty much gone by the time Campbell was in his mid-20's.

The world seems distorted by the narrative voice -- but often in Campbell, distortion is objective and not subjective within the story. Terrible things are breaking through into one's perceptions. It's a career-spanning signature that renders the Lovecraftian idea of reality being attacked in descriptive rather than expositional terms.

Thankfully, Campbell has a sense of humour as well (and indeed wrote pretty much the only funny serial killer novel I can think of, The Count of Eleven, in which humour and sadness feed off each other in illuminating ways). "The Word" is probably the funniest story here, but it also follows the first-person descent of its unlikeable narrator into madness. Or perhaps not.

All within a story involving science-fiction conventions, self-help gurus, and New-Age 'wisdom.' Somehow it all ends up being one of the scarier investigations of the long-lived sub-genre of The Forbidden Book that I can think of. I mean, what if the Necronomicon came disguised as The Celestine Prophecy? What if the Necronomicon always comes disguised as The Celestine Prophecy (or The Shack, or The Secret, or...)...?

Other standouts here include "The Retrospective", in which going home turns out to be a bad idea; "The Entertainment", in which figures a senior citizens' home with peculiar ideas about nightly entertainment for its residents; and "Never to be Heard", in which choral music plays a singular part. Places that turn out to be places one shouldn't have gone include trains, highways, schools, carnivals, old movie houses, and, of course, one's boring job. Highly recommended.

Thursday, January 31, 2013

Tuesday, January 29, 2013

Groove is in the Heart

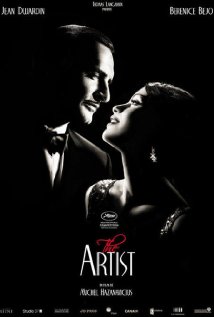

The Artist: written and directed by Michel Hazanavicius: starring Jean Dujardin (George Valentin), Berenice Bejo (Peppy Miller), John Goodman (Al Zimmer), and James Cromwell (Clifton) (2011): Hollywood tends to like its metanarratives peppy and upbeat when it's going to reward them with Oscars, and on the surface last year's Best Picture winner is just that. There's an underlying thread of despair, though, reminiscent of the sort of thing one sometimes found in Charlie Chaplin movies. Thankfully, the abyss is kept at bay with slapstick, dancing, and some awfully good scenes involving a dog.

This mostly silent movie (there's a score and sound effects and voices at key moments), shot in colour but presented entirely in period-appropriate black and white (and in a period-appropriate 1:1.33 aspect ratio) is a delight about the last days of silent motion pictures and the first few years of sound in Hollywood. Box-office king George Valentin, loosely based on Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., finds himself a relic of the past. The ingenue he discovered, Peppy White, finds herself becoming a big star.

The plot bears some similarity to the oft-filmed chestnut A Star is Born. Shot and staged like a late-silent-era movie, we get a certain amount of approriate mugging, a heroic dog with several killer scenes (one in which he fetches a police officer is a lovely bit of business worthy of a Chaplin or a Keaton), and a host of actors who look pretty much absolutely right for the time period and the way films looked back then. The French stars look great, while the Hollywood supporting actors -- most notably John Goodman and James Cromwell -- have the sort of faces that work perfectly in this milieu.

While there are also parallels between the plot of The Artist and Singing in the Rain, the number of allusions and references is broader than that. One will see shades of some of F.W. Murnau's films, Sunset Boulevard, Citizen Kane, City Lights, a musical quote from Vertigo, and a number of Guy Maddin films that play in the same sandbox. But you don't need a background in film to enjoy these references and salutes: The Artist is a delight on its own, and a delight from beginning to end. Highly recommended.

This mostly silent movie (there's a score and sound effects and voices at key moments), shot in colour but presented entirely in period-appropriate black and white (and in a period-appropriate 1:1.33 aspect ratio) is a delight about the last days of silent motion pictures and the first few years of sound in Hollywood. Box-office king George Valentin, loosely based on Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., finds himself a relic of the past. The ingenue he discovered, Peppy White, finds herself becoming a big star.

The plot bears some similarity to the oft-filmed chestnut A Star is Born. Shot and staged like a late-silent-era movie, we get a certain amount of approriate mugging, a heroic dog with several killer scenes (one in which he fetches a police officer is a lovely bit of business worthy of a Chaplin or a Keaton), and a host of actors who look pretty much absolutely right for the time period and the way films looked back then. The French stars look great, while the Hollywood supporting actors -- most notably John Goodman and James Cromwell -- have the sort of faces that work perfectly in this milieu.

While there are also parallels between the plot of The Artist and Singing in the Rain, the number of allusions and references is broader than that. One will see shades of some of F.W. Murnau's films, Sunset Boulevard, Citizen Kane, City Lights, a musical quote from Vertigo, and a number of Guy Maddin films that play in the same sandbox. But you don't need a background in film to enjoy these references and salutes: The Artist is a delight on its own, and a delight from beginning to end. Highly recommended.

Monday, January 28, 2013

The Real Monster Homes of Maine

Hell House by Richard Matheson (1970): Matheson's great ghost story pays homage to Shirley Jackson's earlier, great haunted-house novel, The Haunting of Hill House, in many of its attributes. As in Jackson's novel, Hell House gives us a quartet of psychic investigators led by an academic and weighed down by personal issues who've been brought together to stay in an extremely haunted house for several days.

Matheson's novel focuses on the always fuzzy world of "psychic research" far more than Jackson's did. The psychosexual issues are much more overt. And unlike Hill House, where the haunting seemed to be a matter of a Bad Place rather than individual Bad Ghosts, Hell House appears to be the domain of the ghost of Emeric Belasco. Matheson loosely bases Belasco on Aleister Crowley, black magician and self-proclaimed "wickedest man in the world." Belaso is much wickeder: his remote Maine mansion was the site of mass murder, suicide, and worse. But when the authorities finally broke into the mansion in the 1920's, Belasco was nowhere to be found among the dead.

Hell House is set in 1970. Two previous attempts to probe the mysteries of Hell House, the last in 1940, ended in the deaths or institutionalization of all those involved but one. And that one, a then-16-year-old boy judged to be one of the greatest psychics ever, is along for this expedition. Why? Because a dying millionaire is paying him and the others $100,000 each to try to figure out from the evidence of Hell House whether the human soul survives death.

As with his great, rational vampire novel I am Legend, Matheson herein sails the edge between the supernatural and the scientific. The physics professor who leads the expedition believes that ghosts are a product of human minds interacting with a charged psychic environment left behind by traumatic events in a specific location. There is no life after death except as an amorphous energy field subject to the fears and hopes of the living. The academic's wife isn't so sure. And the two psychics know that there's something more than that going on. But what?

Matheson doesn't write 'long.' Hell House is fairly brief and to-the-point, and its structure is as much mystery novel as horror novel. But the horrors are quite potent, and the characters sympathetically drawn even as they wrestle with their fears and their failings. Highly recommended.

Matheson's novel focuses on the always fuzzy world of "psychic research" far more than Jackson's did. The psychosexual issues are much more overt. And unlike Hill House, where the haunting seemed to be a matter of a Bad Place rather than individual Bad Ghosts, Hell House appears to be the domain of the ghost of Emeric Belasco. Matheson loosely bases Belasco on Aleister Crowley, black magician and self-proclaimed "wickedest man in the world." Belaso is much wickeder: his remote Maine mansion was the site of mass murder, suicide, and worse. But when the authorities finally broke into the mansion in the 1920's, Belasco was nowhere to be found among the dead.

Hell House is set in 1970. Two previous attempts to probe the mysteries of Hell House, the last in 1940, ended in the deaths or institutionalization of all those involved but one. And that one, a then-16-year-old boy judged to be one of the greatest psychics ever, is along for this expedition. Why? Because a dying millionaire is paying him and the others $100,000 each to try to figure out from the evidence of Hell House whether the human soul survives death.

As with his great, rational vampire novel I am Legend, Matheson herein sails the edge between the supernatural and the scientific. The physics professor who leads the expedition believes that ghosts are a product of human minds interacting with a charged psychic environment left behind by traumatic events in a specific location. There is no life after death except as an amorphous energy field subject to the fears and hopes of the living. The academic's wife isn't so sure. And the two psychics know that there's something more than that going on. But what?

Matheson doesn't write 'long.' Hell House is fairly brief and to-the-point, and its structure is as much mystery novel as horror novel. But the horrors are quite potent, and the characters sympathetically drawn even as they wrestle with their fears and their failings. Highly recommended.

Sunday, January 27, 2013

Small-town Bringdown

'Salem's Lot: adapted by Peter Filardi from the novel by Stephen King; directed by Mikael Salomon; starring Rob Lowe (Ben Mears), Andre Braugher (Matt Burke), Donald Sutherland (Straker), Samantha Mathis (Susan Norton), Robert Mammone (Dr. James Cody), Dan Byrd (Mark Petrie), James Cromwell (Father Callahan) and Rutger Hauer (Barlow) (2004): Very enjoyable, mildly unfaithful TNT miniseries adaptation of King's vampire novel could use another 80 minutes (which would have made it a 6-hour rather than a 4-hour miniseries). Most of that extra time could have been beneficially front-loaded: as is, we've really only scratched the surface with the main characters before we're headlong into the vampire narrative.

The most obvious change is that the story is now set in 2004 rather than 1975. There are the usual, necessary character conflations when dealing with a long novel (one sub-plot involving marital infidelity has been folded into the story of Dr. James Cody) and several pretty effective shifts made so as to show the viewer certain bad behaviours rather than explain different, more complicated behaviours, as the novel can do and a movie generally can't without a lengthy bit of spoken-word exposition. The small town of Salem's Lot comes across as more blatantly sinful than in the book, but that's partially because of the narrative compression. In any case, the evil from without still manifests itself at least partially as a mirror image of the evil within.

Rob Lowe does nice, nuanced work as protagonist Ben Mears -- watch this and an episode of Parks and Recreation to realize what a sharp actor he's become, handicapped though he is by being prettier than most of his female leads. Andre Braugher -- as Van Helsingesque English Teacher Matt Burke -- is solid and dependable in a somewhat underwritten role, while Samantha Mathis, Dan Byrd and Robert Mammone also do solid work as the unlikely, reluctant, disbelieving vampire fighters. Donald Sutherland plays the vampire's human henchman as a somewhat antic lunatic, more Renfield than the novel's version. Rutger Hauer wisely underplays Barlow the vampire, and the miniseries doesn't force him to deliver some of the novel's Dracula-esque Barlow lines, easily the weakest part of King's novel.

The filmmakers drop King's homage to Tolkien -- in the novel, crosses and holy water glow "with an elvish light" when a vampire is near. I think that's unfortunate, as one scene that uses that glow in the novel seems perfectly suited to filming (Father Callahan's confrontation with Barlow at the Petrie household). Creatures crawling across ceilings also don't have the same zing as they once did. There is something cool about the movie's depiction of vampire death, though, drawing as the visual effect does on a deflating balloon sputtering around.

Overall, there are a lot of good scares here and, because of changes made from the novel, a certain number of surprises awaiting King readers as well. Maybe the smartest decision made was to incorporate stretches of the novel's third-person narration as the first-person narration of Ben Mears. It's very effective, especially during the movie's opening and closing scenes. Recommended.

The most obvious change is that the story is now set in 2004 rather than 1975. There are the usual, necessary character conflations when dealing with a long novel (one sub-plot involving marital infidelity has been folded into the story of Dr. James Cody) and several pretty effective shifts made so as to show the viewer certain bad behaviours rather than explain different, more complicated behaviours, as the novel can do and a movie generally can't without a lengthy bit of spoken-word exposition. The small town of Salem's Lot comes across as more blatantly sinful than in the book, but that's partially because of the narrative compression. In any case, the evil from without still manifests itself at least partially as a mirror image of the evil within.

Rob Lowe does nice, nuanced work as protagonist Ben Mears -- watch this and an episode of Parks and Recreation to realize what a sharp actor he's become, handicapped though he is by being prettier than most of his female leads. Andre Braugher -- as Van Helsingesque English Teacher Matt Burke -- is solid and dependable in a somewhat underwritten role, while Samantha Mathis, Dan Byrd and Robert Mammone also do solid work as the unlikely, reluctant, disbelieving vampire fighters. Donald Sutherland plays the vampire's human henchman as a somewhat antic lunatic, more Renfield than the novel's version. Rutger Hauer wisely underplays Barlow the vampire, and the miniseries doesn't force him to deliver some of the novel's Dracula-esque Barlow lines, easily the weakest part of King's novel.

The filmmakers drop King's homage to Tolkien -- in the novel, crosses and holy water glow "with an elvish light" when a vampire is near. I think that's unfortunate, as one scene that uses that glow in the novel seems perfectly suited to filming (Father Callahan's confrontation with Barlow at the Petrie household). Creatures crawling across ceilings also don't have the same zing as they once did. There is something cool about the movie's depiction of vampire death, though, drawing as the visual effect does on a deflating balloon sputtering around.

Overall, there are a lot of good scares here and, because of changes made from the novel, a certain number of surprises awaiting King readers as well. Maybe the smartest decision made was to incorporate stretches of the novel's third-person narration as the first-person narration of Ben Mears. It's very effective, especially during the movie's opening and closing scenes. Recommended.

Saturday, January 26, 2013

Rise of the Super-Communist

Superman: Red Son: written by Mark Millar; illustrated by Dave Johnson, Kilian Plunkett, Andrew Robinson and Walden Wong (2003): What if Superman's rocket landed in Stalin's USSR in the 1930's? That's the initial changed premise in this Elseworlds 'What if?' story of a Communist Superman and his crusade to keep everyone on the planet safe, all the time, whether they want him to or not.

It's a much-praised story that riffs an awful lot on a classic Silver-Age Superman 'Imaginary Story' in which Superman, concerned by his failures, exposes himself to a barrage of various types of Kryptonite radiation and ends up splitting into two mono-coloured versions of himself, Superman-Red and Superman-Blue. They're both about 100 times smarter than the original, and thus proceed to eliminate all crime, disease, poverty, and want from Earth in about a week. That was presented as a utopia. What's presented here is also a utopia unless one wants a certain level of freedom.

Superman's powers here are actually greater than pretty much any other version of the character in comic books: he actually can protect everyone on the planet from even relatively small-scale dangers such as car accidents. This causes people to start driving recklessly in great numbers (!!!). Once the Soviet Man of Steel takes over from Stalin, the countries of the world join the Communist Bloc with the exception of the United States. Lex Luthor helps keep the U.S. free while trying to figure out how to stop Superman. Some heroes join Superman (Wonder Woman being the prime example) while others are deployed against him (Green Lantern and Batman).

It's all fairly enjoyable, though I'm not entirely sure why this is praised as much as it is: besides Superman-Red/Superman-Blue, there's a Marvel graphic novel from the 1980's, Emperor Doom, which covers pretty much the same territory in about 1/3 the space, while Alan Moore's Marvelman (aka Miracleman) epic also ends in similar territory, only with much better writing.

Time constraints also forced an art change with the last third of the collected book (the third issue of the three issue miniseries in its original printing). Dave Johnson's work is cleaner and more suited to the narrative, making the change a bit jarring when the art switches to Kilian Plunkett. The twist ending is nice, if a bit gimmicky and telegraphed a bit too much in the closing pages. Lightly recommended.

It's a much-praised story that riffs an awful lot on a classic Silver-Age Superman 'Imaginary Story' in which Superman, concerned by his failures, exposes himself to a barrage of various types of Kryptonite radiation and ends up splitting into two mono-coloured versions of himself, Superman-Red and Superman-Blue. They're both about 100 times smarter than the original, and thus proceed to eliminate all crime, disease, poverty, and want from Earth in about a week. That was presented as a utopia. What's presented here is also a utopia unless one wants a certain level of freedom.

Superman's powers here are actually greater than pretty much any other version of the character in comic books: he actually can protect everyone on the planet from even relatively small-scale dangers such as car accidents. This causes people to start driving recklessly in great numbers (!!!). Once the Soviet Man of Steel takes over from Stalin, the countries of the world join the Communist Bloc with the exception of the United States. Lex Luthor helps keep the U.S. free while trying to figure out how to stop Superman. Some heroes join Superman (Wonder Woman being the prime example) while others are deployed against him (Green Lantern and Batman).

It's all fairly enjoyable, though I'm not entirely sure why this is praised as much as it is: besides Superman-Red/Superman-Blue, there's a Marvel graphic novel from the 1980's, Emperor Doom, which covers pretty much the same territory in about 1/3 the space, while Alan Moore's Marvelman (aka Miracleman) epic also ends in similar territory, only with much better writing.

Time constraints also forced an art change with the last third of the collected book (the third issue of the three issue miniseries in its original printing). Dave Johnson's work is cleaner and more suited to the narrative, making the change a bit jarring when the art switches to Kilian Plunkett. The twist ending is nice, if a bit gimmicky and telegraphed a bit too much in the closing pages. Lightly recommended.

Labels:

dave johnson,

dystopia,

elseworlds,

kilian plunkett,

mark millar,

marvelman,

miracleman,

red son,

stalin,

superman,

ussr,

utopia,

what if

Wednesday, January 23, 2013

Into the Woods

The Ritual by Adam Nevill (2011): Four British friends (Luke, Dom, Phil, and Hutch) who first met in university 15 years earlier decide to go camping in Sweden for their 15th anniversary reunion. Tensions start to run a bit high, as Luke begins to chafe at what he feels is the derogatory attitude of two of the others to his low-income, high-freedom lifestyle. But when the group finds an animal so mutilated as to be unrecognizable hanging fifteen feet up in a tree, social frictions gradually start to seem less important. Something is out there, and they are lost because the most competent of them decided to try a short-cut. Oops.

In the small but sturdy sub-genre of 'camping trips gone wrong', The Ritual is a humdinger. Nevill has a sure hand with characterization, giving all the characters reasons for their behaviour, and eliciting sympathy in the face of whatever it is that's out there just beyond the firelight.

One of the things that elevates The Ritual above the run-of-the-mill is Nevill's careful attention to describing the problems of navigating a forest that hasn't been navigated by people for hundreds of years, if ever. His characters are pursued through a forest that has reduced their speed to a near-crawl. Whatever it is that pursues them is never seen clearly. And the forest seems only to want them to go on one specific path -- to a moldering house, an ancient graveyard complete with an ancient dolmen and a passage graveyard, and beyond.

There are glimpses of something in the trees improbably big, and sounds of trees crashing down in the distance. Food and water run scarce. Two of the four are injured and unable to make good time. Night keeps arrving too soon.

Nevill acknowledges the influences of both fiction and non-fiction work -- this may be one of the first novels to owe a debt to both Into the Wild and Arthur Machen's "The White People." But this is a striking work on its own, perhaps in need of a bit of trimming in its second half, but overall a riveting horror novel. Highly recommended.

In the small but sturdy sub-genre of 'camping trips gone wrong', The Ritual is a humdinger. Nevill has a sure hand with characterization, giving all the characters reasons for their behaviour, and eliciting sympathy in the face of whatever it is that's out there just beyond the firelight.

One of the things that elevates The Ritual above the run-of-the-mill is Nevill's careful attention to describing the problems of navigating a forest that hasn't been navigated by people for hundreds of years, if ever. His characters are pursued through a forest that has reduced their speed to a near-crawl. Whatever it is that pursues them is never seen clearly. And the forest seems only to want them to go on one specific path -- to a moldering house, an ancient graveyard complete with an ancient dolmen and a passage graveyard, and beyond.

There are glimpses of something in the trees improbably big, and sounds of trees crashing down in the distance. Food and water run scarce. Two of the four are injured and unable to make good time. Night keeps arrving too soon.

Nevill acknowledges the influences of both fiction and non-fiction work -- this may be one of the first novels to owe a debt to both Into the Wild and Arthur Machen's "The White People." But this is a striking work on its own, perhaps in need of a bit of trimming in its second half, but overall a riveting horror novel. Highly recommended.

Labels:

adam nevill,

camping,

deliverance,

hiking,

into the wild,

sweden,

the ritual,

the white people

Don't Let Them In

'Salem's Lot by Stephen King (1975): Stephen King's second published novel did at least two new things I can think of: it collided the vampire novel with a sweeping character study of an entire town (as many have noted, it's Dracula meets Peyton Place); and it codified the role of the Familiar in a vampire's life in a way that many subsequent novelists treat as if it were derived from vampire mythology. King extrapolates the role of Straker in this novel from Renfield in Dracula and Renfield/Harker's altered role in the Bela Lugosi Dracula.

Later works such as Fright Night (1985) and Justin Cronin's The Passage and The Twelve would run with the idea of a non-vampiric helper paving the way for the vampire. That Straker also has to perform certain rituals to let the vampire Barlow into the town of (Jeru)'salem's Lot also seems new to me.

The novel still purrs along like a dream. Some elements (the rapid development of love between protagonist Ben Mears and townie Susan Norton) come a bit too fast, even in a lengthy novel such as this. But both major characters (struggling novelist Mears, who's returned to the town at pretty much the worst time ever; Father Callahan) and minor (the sheriff, especially) are fleshed out with great sympathy and precision, or at least empathy.

King wisely keeps the vampire Barlow off-stage for much of the novel -- the few times when Barlow talks (or writes) are also a bit weak, as King has borrowed pretty much all of Barlow's attributes from the Dracula 101 class of king-vampire characterization. Straker, the Familiar, is much more interesting. Highly recommended.

Later works such as Fright Night (1985) and Justin Cronin's The Passage and The Twelve would run with the idea of a non-vampiric helper paving the way for the vampire. That Straker also has to perform certain rituals to let the vampire Barlow into the town of (Jeru)'salem's Lot also seems new to me.

The novel still purrs along like a dream. Some elements (the rapid development of love between protagonist Ben Mears and townie Susan Norton) come a bit too fast, even in a lengthy novel such as this. But both major characters (struggling novelist Mears, who's returned to the town at pretty much the worst time ever; Father Callahan) and minor (the sheriff, especially) are fleshed out with great sympathy and precision, or at least empathy.

King wisely keeps the vampire Barlow off-stage for much of the novel -- the few times when Barlow talks (or writes) are also a bit weak, as King has borrowed pretty much all of Barlow's attributes from the Dracula 101 class of king-vampire characterization. Straker, the Familiar, is much more interesting. Highly recommended.

Labels:

barlow,

dracula,

peyton place,

salem's lot,

stephen king,

the familiar,

vampires

Saturday, January 19, 2013

Weird Heroes

Harbinger Volume 1: Omega Rising: written by Joshua Dysart; illustrated by Khari Evans and others (2012): Enjoyable reboot of the early 1990's Valiant line's entry in the telepathic superman sweepstakes. Joshua Dysart keeps things moving while also supplying quite a bit of background and characterization, along with a likeable protagonist who does one truly awful (but understandable) thing early and then tries to make up for it ever afterwards.

Thankfully, there's an emphasis on the science-fictional and political aspects of the whole 'secret race of telepaths' concept, with more traditional superhero battles taking a back seat. The art, mostly by Khari Evans, is clean and straightforward, and he seems to have a nice command of panel-to-panel continuity. Recommended.

The Rocketeer: Cargo of Doom: written by Mark Waid; illustrated by Chris Samnee (2012): Waid and Samnee try their hands at what I think is the first multi-issue Rocketeer storyline since late creator/writer/artist Dave Stevens' second Rocketeer serial of the late 1980's. Waid captures the breezy, 1930's pulp quality of Stevens while adding a couple of new characters to the cast.

Waid also brings in yet another established pulp character to the Rocketeer's world without ever quite naming said character due to copyright concerns (Doc Savage and his assistants Monk and Ham appeared this way in the first Rocketeer adventure, with the Shadow and his associates following suit in the second; Disney replaced Doc Savage with Howard Hughes for the 1991 Rocketeer movie). Here, it's Doc Savage villain John Sunlight. Also dinosaurs. Samnee's art reminds me more of Steve Rude than Dave Stevens, but that's fine -- it still looks pretty good, and pretty much period-appropriate. Recommended.

Jonah Hex: Two-Gun Mojo: written by Joe R. Lansdale; illustrated by Timothy Truman and Sam Glanzman (1993): Long-time horror and Western writer Joe Lansdale's first outing on DC's Western anti-hero Jonah Hex is a lot of grimy fun, with Tim Truman and Sam Glanzman supplying suitably gritty, violent visuals.

Looking to avenge the murder of a fellow bounty hunter, the disfigured Civil War veteran fights what may or may not be a supernatural threat hiding within a travelling carnival. Can the boss of the carnival actually animate the dead, or are his tricks explainable through rational means? In any event, Hex finds himself stuck between Apache raiding parties, a bounty on his head for a murder he didn't commit, and what appears to be Zombie Wild Bill Hickok.

The Truman/Glanzman art team is squarely in the tradition of Hex's longtime illustrator Tony deZuniga without being imitative, and as this miniseries was aimed at adults, they're allowed a lot more leeway to depict violence and its consequences. Jonah Hex himself is, as always, oddly noble. He may have started life as a knock-off of Clint Eastwood's Man with No Name, but he's his own character now. Recommended.

Tomorrow Stories Volume 2: written by Alan Moore; illustrated by Melinda Gebbie, Kevin Nowlan, Jim Baikie, Rick Veitch, Hilary Barta, and others (2000-2002): One of two books in Alan Moore's ABC Comics line of the early oughts that resurrected the anthology title, with this one leaning more heavily on comedy and pastiche than the other (Tom Strong's Terrific Tales). Kevin Nowlan's art on the Jack Quick series won him an Eisner Award for art, and it is a heckuva performance from an artist who doesn't do that much pencilling.

Tomorrow Stories Volume 2: written by Alan Moore; illustrated by Melinda Gebbie, Kevin Nowlan, Jim Baikie, Rick Veitch, Hilary Barta, and others (2000-2002): One of two books in Alan Moore's ABC Comics line of the early oughts that resurrected the anthology title, with this one leaning more heavily on comedy and pastiche than the other (Tom Strong's Terrific Tales). Kevin Nowlan's art on the Jack Quick series won him an Eisner Award for art, and it is a heckuva performance from an artist who doesn't do that much pencilling.

The different strips that appeared over the course of 12 issues tended to be parodies and/or homages to either very specific antecedents (Moore and Rick Veitch's Greyshirt is a stylistic homage to Will Eisner's Spirit both in writing and in visuals) or more general comic-book and pop-culture sources (Jack Quick parodies 'smart kid' strips and books, The First American parodies patriotic superhero strips, Splash Brannigan homages both Plastic Man and the Mad comic book of the 1950's). The Cobweb, with its sexually adventurous female crimefighter, spreads a wider net, allowing for everything from 19th century woodcuts to fumetti with talking action figures. Recommended.

Thankfully, there's an emphasis on the science-fictional and political aspects of the whole 'secret race of telepaths' concept, with more traditional superhero battles taking a back seat. The art, mostly by Khari Evans, is clean and straightforward, and he seems to have a nice command of panel-to-panel continuity. Recommended.

The Rocketeer: Cargo of Doom: written by Mark Waid; illustrated by Chris Samnee (2012): Waid and Samnee try their hands at what I think is the first multi-issue Rocketeer storyline since late creator/writer/artist Dave Stevens' second Rocketeer serial of the late 1980's. Waid captures the breezy, 1930's pulp quality of Stevens while adding a couple of new characters to the cast.

Waid also brings in yet another established pulp character to the Rocketeer's world without ever quite naming said character due to copyright concerns (Doc Savage and his assistants Monk and Ham appeared this way in the first Rocketeer adventure, with the Shadow and his associates following suit in the second; Disney replaced Doc Savage with Howard Hughes for the 1991 Rocketeer movie). Here, it's Doc Savage villain John Sunlight. Also dinosaurs. Samnee's art reminds me more of Steve Rude than Dave Stevens, but that's fine -- it still looks pretty good, and pretty much period-appropriate. Recommended.

Jonah Hex: Two-Gun Mojo: written by Joe R. Lansdale; illustrated by Timothy Truman and Sam Glanzman (1993): Long-time horror and Western writer Joe Lansdale's first outing on DC's Western anti-hero Jonah Hex is a lot of grimy fun, with Tim Truman and Sam Glanzman supplying suitably gritty, violent visuals.

Looking to avenge the murder of a fellow bounty hunter, the disfigured Civil War veteran fights what may or may not be a supernatural threat hiding within a travelling carnival. Can the boss of the carnival actually animate the dead, or are his tricks explainable through rational means? In any event, Hex finds himself stuck between Apache raiding parties, a bounty on his head for a murder he didn't commit, and what appears to be Zombie Wild Bill Hickok.

The Truman/Glanzman art team is squarely in the tradition of Hex's longtime illustrator Tony deZuniga without being imitative, and as this miniseries was aimed at adults, they're allowed a lot more leeway to depict violence and its consequences. Jonah Hex himself is, as always, oddly noble. He may have started life as a knock-off of Clint Eastwood's Man with No Name, but he's his own character now. Recommended.

Tomorrow Stories Volume 2: written by Alan Moore; illustrated by Melinda Gebbie, Kevin Nowlan, Jim Baikie, Rick Veitch, Hilary Barta, and others (2000-2002): One of two books in Alan Moore's ABC Comics line of the early oughts that resurrected the anthology title, with this one leaning more heavily on comedy and pastiche than the other (Tom Strong's Terrific Tales). Kevin Nowlan's art on the Jack Quick series won him an Eisner Award for art, and it is a heckuva performance from an artist who doesn't do that much pencilling.

Tomorrow Stories Volume 2: written by Alan Moore; illustrated by Melinda Gebbie, Kevin Nowlan, Jim Baikie, Rick Veitch, Hilary Barta, and others (2000-2002): One of two books in Alan Moore's ABC Comics line of the early oughts that resurrected the anthology title, with this one leaning more heavily on comedy and pastiche than the other (Tom Strong's Terrific Tales). Kevin Nowlan's art on the Jack Quick series won him an Eisner Award for art, and it is a heckuva performance from an artist who doesn't do that much pencilling.The different strips that appeared over the course of 12 issues tended to be parodies and/or homages to either very specific antecedents (Moore and Rick Veitch's Greyshirt is a stylistic homage to Will Eisner's Spirit both in writing and in visuals) or more general comic-book and pop-culture sources (Jack Quick parodies 'smart kid' strips and books, The First American parodies patriotic superhero strips, Splash Brannigan homages both Plastic Man and the Mad comic book of the 1950's). The Cobweb, with its sexually adventurous female crimefighter, spreads a wider net, allowing for everything from 19th century woodcuts to fumetti with talking action figures. Recommended.

Tuesday, January 15, 2013

Invasions and Degradations

It Came from Outer Space: adapted by Harry Essex from a short story by Ray Bradbury; directed by Jack Arnold; starring Richard Carlson (John Putnam), Barbara Rush (Ellen Fields), Charles Drake (Sheriff) and Russell Johnson (George) (1953): Surprisingly thoughtful and methodically paced 1950's alien-invasion movie from the great Jack Arnold, with an assist from Ray Bradbury, who actually wrote much of the screenplay.

The Arizona landscapes make a perfect backdrop for a story of paranoia and infiltration that doesn't go where one might expect it to, given its Cold War origins. That's the Professor from Gilligan's Island (Russell Johnson) as a power lineman. If any screen aliens are the parents of Kodos and Kang from The Simpsons, it's these aliens. Recommended.

The Raven: written by Hannah Shakespeare and Ben Livingston; directed by James McTeigue; starring John Cusack (Edgar Allan Poe), Luke Evans (Detective Fields), Alice Eve (Emily Hamilton) and Brendan Gleeson (Captain Hamilton) (2012): Often jarringly anachronistic dialogue is the only major problem with this solid period thriller (it's set in Baltimore in the late 1840's). John Cusack makes an interesting Edgar Allan Poe, doomed (as history and the opening scene tell us) to die under mysterious circumstances within days of the movie's beginning.

But first he has to help a police detective stop a serial killer who's modelling his killings on Poe's short stories. Things look great, and the direction is moody and effective from V for Vendetta 's McTeigue. But boy, the dialogue stinks at points, and there are also several points at which the writers seem to lack a basic knowledge of Poe's body of work (when asked if he'd ever written about sailors, Poe says no, apparently forgetting The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym, "The Murders in the Rue Morgue", and about half-a-dozen other stories. Well, he is drunk and opium-besotted much of the time).

Luke Evans is also effective as a hyper-rational detective right out of a Poe -- C. Auguste Dupin, to be exact, the fictional ancestor of Sherlock Holmes. Oh, and there's no Oran-Outan in the movie, dammit, though Poe does have a pet raccoon whose fate is left unresolved at the end of the film. They've also got Jules Verne (who homaged Poe in From the Earth to the Moon with the space-faring Baltimore Gun Club) starting his writing career about 20 years early. Either that or the serial killer is also a time traveller. Recommended.

The Arizona landscapes make a perfect backdrop for a story of paranoia and infiltration that doesn't go where one might expect it to, given its Cold War origins. That's the Professor from Gilligan's Island (Russell Johnson) as a power lineman. If any screen aliens are the parents of Kodos and Kang from The Simpsons, it's these aliens. Recommended.

The Raven: written by Hannah Shakespeare and Ben Livingston; directed by James McTeigue; starring John Cusack (Edgar Allan Poe), Luke Evans (Detective Fields), Alice Eve (Emily Hamilton) and Brendan Gleeson (Captain Hamilton) (2012): Often jarringly anachronistic dialogue is the only major problem with this solid period thriller (it's set in Baltimore in the late 1840's). John Cusack makes an interesting Edgar Allan Poe, doomed (as history and the opening scene tell us) to die under mysterious circumstances within days of the movie's beginning.

But first he has to help a police detective stop a serial killer who's modelling his killings on Poe's short stories. Things look great, and the direction is moody and effective from V for Vendetta 's McTeigue. But boy, the dialogue stinks at points, and there are also several points at which the writers seem to lack a basic knowledge of Poe's body of work (when asked if he'd ever written about sailors, Poe says no, apparently forgetting The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym, "The Murders in the Rue Morgue", and about half-a-dozen other stories. Well, he is drunk and opium-besotted much of the time).

Luke Evans is also effective as a hyper-rational detective right out of a Poe -- C. Auguste Dupin, to be exact, the fictional ancestor of Sherlock Holmes. Oh, and there's no Oran-Outan in the movie, dammit, though Poe does have a pet raccoon whose fate is left unresolved at the end of the film. They've also got Jules Verne (who homaged Poe in From the Earth to the Moon with the space-faring Baltimore Gun Club) starting his writing career about 20 years early. Either that or the serial killer is also a time traveller. Recommended.

Story Time

Science Fiction Omnibus: edited by Groff Conklin, containing the following stories: "A Subway Named Mobius" by A.J. Deutsch; "The Colour Out of Space" by H.P. Lovecraft; "The Star Dummy" by Anthony Boucher; "Homo Sol" by Isaac Asimov; "Kaleidoscope" by Ray Bradbury; "Plague" by Murray Leinster; "Test Piece" by Eric Frank Russell; "Spectator Sport" by John D. MacDonald; "The Weapon" by Fredric Brown; "History Lesson" by Arthur C. Clarke; and "Instinct" by Lester Del Rey (Collected 1956): Enjoyable, idiosyncratic anthology of mostly 1940's and 1950's science fiction from the once ubiquitous and always good Groff Conklin.

The two most-anthologized stories here are the Lovecraft and Bradbury offerings. John D. MacDonald, best known for his Travis Magee mystery novels, was also a prolific science-fiction writer in the 1950's, and his short-short story anticipates virtual reality in a startling and prescient way. Somewhat bizarrely, the Boucher story anticipates Alf! The rest of the stories are solid, with the Arthur Clarke offering probably having the funniest ending, as Venusians make some extremely wrong conclusions about the now-extinct Earth society based on one surviving film strip. Recommended.

Selected Stories of Philip K. Dick: edited and with an introduction by Jonathan Lethem; containing the following stories: "Beyond Lies the Wub"; "Roog"; "Paycheck"; "Second Variety"; "Impostor"; "The King of the Elves"; "Adjustment Team"; "Foster, You're Dead!"; "Upon the Dull Earth"; "Autofac"; "The Minority Report"; "The Days of Perky Pat"; "Precious Artifact"; "A Game of Unchance"; "We Can Remember It for You Wholesale"; "Faith of Our Fathers"; "The Electric Ant"; "A Little Something for Us Tempunauts"; "The Exit Door Leads In"; "Rautavaara's Case"; "I Hope I Shall Arrive Soon" (aka "Frozen Journey") (Collected 2002):

Any Dick short-story collection will be pretty good, as he wrote very few stinkers during his prolific career. Lethem leans a bit too much towards the science-fictional here, including one truly minor story ("The Exit Door Leads In", an unusually defeatist story, even for Dick) and excluding two of Dick's best horror stories, the stunning "The Father Thing", which I'd nominate as at least one of the 20 scariest stories ever written in English, and the creepily droll "The Cookie Lady", a Dickian exercise in dark Bradburyian whimsy.

I'd also have included Dick's hilarious 1950's story in which Scientology has become the world's leading religion. If you keep score of these things, pretty much every Dick short story ever adapted into a movie is represented here ("Paycheck"; "Second Variety" (as Screamers and its sequels) ; "Impostor"; "Adjustment Team" (as The Adjustment Bureau); "The Minority Report" and "We Can Remember It for You Wholesale" (twice as Total Recall)). Highly recommended, though the collection may whet your appetite for a more comprehensive survey of Dick's writing. Thankfully, he's pretty much entirely in print.

The two most-anthologized stories here are the Lovecraft and Bradbury offerings. John D. MacDonald, best known for his Travis Magee mystery novels, was also a prolific science-fiction writer in the 1950's, and his short-short story anticipates virtual reality in a startling and prescient way. Somewhat bizarrely, the Boucher story anticipates Alf! The rest of the stories are solid, with the Arthur Clarke offering probably having the funniest ending, as Venusians make some extremely wrong conclusions about the now-extinct Earth society based on one surviving film strip. Recommended.

Selected Stories of Philip K. Dick: edited and with an introduction by Jonathan Lethem; containing the following stories: "Beyond Lies the Wub"; "Roog"; "Paycheck"; "Second Variety"; "Impostor"; "The King of the Elves"; "Adjustment Team"; "Foster, You're Dead!"; "Upon the Dull Earth"; "Autofac"; "The Minority Report"; "The Days of Perky Pat"; "Precious Artifact"; "A Game of Unchance"; "We Can Remember It for You Wholesale"; "Faith of Our Fathers"; "The Electric Ant"; "A Little Something for Us Tempunauts"; "The Exit Door Leads In"; "Rautavaara's Case"; "I Hope I Shall Arrive Soon" (aka "Frozen Journey") (Collected 2002):

Any Dick short-story collection will be pretty good, as he wrote very few stinkers during his prolific career. Lethem leans a bit too much towards the science-fictional here, including one truly minor story ("The Exit Door Leads In", an unusually defeatist story, even for Dick) and excluding two of Dick's best horror stories, the stunning "The Father Thing", which I'd nominate as at least one of the 20 scariest stories ever written in English, and the creepily droll "The Cookie Lady", a Dickian exercise in dark Bradburyian whimsy.

I'd also have included Dick's hilarious 1950's story in which Scientology has become the world's leading religion. If you keep score of these things, pretty much every Dick short story ever adapted into a movie is represented here ("Paycheck"; "Second Variety" (as Screamers and its sequels) ; "Impostor"; "Adjustment Team" (as The Adjustment Bureau); "The Minority Report" and "We Can Remember It for You Wholesale" (twice as Total Recall)). Highly recommended, though the collection may whet your appetite for a more comprehensive survey of Dick's writing. Thankfully, he's pretty much entirely in print.

Thursday, January 10, 2013

Cry for Love

The Boys Volume 7: The Innocents: written by Garth Ennis; illustrated by Darick Robertson, Russ Braun, and John McCrea (2010): Revelations follow revelations, as Bill Butcher comes to believe Hughie is secretly working for the evil Vought-American corporation because his girlfriend turns out to be a member of premiere superhero group The Seven.

Hughie being Hughie, this is all a coincidence aggravated by Hughie's blithe ignorance of current events and, for that matter, who exactly it is that he and the rest of The Boys are fighting. Hughie's also going to finally find out a different terrible truth about his girlfriend, but only after spending time keeping tabs on Superduper, the only superhero group composed of neither bastards nor poseurs.

That's because, no joke, they're all suffering from major mental health issues which render them benign, loveable, and pretty much harmless. Hughie's relationship with the members of Superduper (a parody of DC's teen supergroup of the 31st century, the Legion of Superheroes) will pay dividends much later in the series. Recommended.

The Boys Volume 10: Butcher, Baker, Candlestickmaker: written by Garth Ennis; illustrated by Darick Robertson (2011): Collection of the six-issue miniseries that finally laid out Boys leader Bill Butcher's tortured personal history. The violence is often overwhelming, as is the tragedy: Butcher is cut from the same mould as Ennis's Saint of Killers in the earlier Preacher series, a violent hardcase redeemed by love and then further damned with the loss of that love. Recommended.

The Boys Volume 11: Over the Hill with the Swords of a Thousand Men: written by Garth Ennis; illustrated by Russ Braun, John McCrea, Keith Burns, and Darick Robertson (2011-2012): The corporate controlled superheroes have decided to take over the world. Well, 65% of them, anyway, while the other 35% lay low and wait to see who wins.

Have Bill Butcher's plans prepared the world to successfully stand against several thousand nigh-invulnerable wankers, or will the vile and vainglorious Homelander soon rule over everything? And which side will corporation Vought-American, which didn't authorize a hostile takeover of the United States by the superheroes it created, come down on as all Hell breaks loose? And will Bill Butcher finally get vengeance upon the Homelander for the rape and subsequent death in (super-powered) childbirth of his wife? And if everything ends here, why is there one more volume to go? Highly recommended.

The Boys Volume 12: The Bloody Doors Off: written by Garth Ennis; illustrated by Garth Ennis, Russ Braun, and Darick Robertson (2012): The six-year, 90-issue, 2000-page odyssey of The Boys ends here, a few months after the blood-soaked superheroic attempt to overthrow the U.S. government. Loveable Scottish Boys member Hughie is still having relationship problems with former superheroine Starlight, more normally referred to as Annie. Vought-American is still up to lots of things, most of them profitable and dreadful. But with armageddon averted, Boys leader Bill Butcher suggests that the Boys take a vacation.

But when a Russian superhero ally of the Boys shows up dead along with a black marketeer, the vacation is cut short. And then the deaths of both supporting and main characters start to mount. Who is tidying up? Was the superhero coup the real threat? Is Hughie capable, mentally and physically, of engaging this newly revealed conspiracy and saving millions or perhaps even billions of lives? Is this Garth Ennis' last superhero comic book? All will be revealed. Highly recommended.

Hughie being Hughie, this is all a coincidence aggravated by Hughie's blithe ignorance of current events and, for that matter, who exactly it is that he and the rest of The Boys are fighting. Hughie's also going to finally find out a different terrible truth about his girlfriend, but only after spending time keeping tabs on Superduper, the only superhero group composed of neither bastards nor poseurs.

That's because, no joke, they're all suffering from major mental health issues which render them benign, loveable, and pretty much harmless. Hughie's relationship with the members of Superduper (a parody of DC's teen supergroup of the 31st century, the Legion of Superheroes) will pay dividends much later in the series. Recommended.

The Boys Volume 10: Butcher, Baker, Candlestickmaker: written by Garth Ennis; illustrated by Darick Robertson (2011): Collection of the six-issue miniseries that finally laid out Boys leader Bill Butcher's tortured personal history. The violence is often overwhelming, as is the tragedy: Butcher is cut from the same mould as Ennis's Saint of Killers in the earlier Preacher series, a violent hardcase redeemed by love and then further damned with the loss of that love. Recommended.

The Boys Volume 11: Over the Hill with the Swords of a Thousand Men: written by Garth Ennis; illustrated by Russ Braun, John McCrea, Keith Burns, and Darick Robertson (2011-2012): The corporate controlled superheroes have decided to take over the world. Well, 65% of them, anyway, while the other 35% lay low and wait to see who wins.

Have Bill Butcher's plans prepared the world to successfully stand against several thousand nigh-invulnerable wankers, or will the vile and vainglorious Homelander soon rule over everything? And which side will corporation Vought-American, which didn't authorize a hostile takeover of the United States by the superheroes it created, come down on as all Hell breaks loose? And will Bill Butcher finally get vengeance upon the Homelander for the rape and subsequent death in (super-powered) childbirth of his wife? And if everything ends here, why is there one more volume to go? Highly recommended.

The Boys Volume 12: The Bloody Doors Off: written by Garth Ennis; illustrated by Garth Ennis, Russ Braun, and Darick Robertson (2012): The six-year, 90-issue, 2000-page odyssey of The Boys ends here, a few months after the blood-soaked superheroic attempt to overthrow the U.S. government. Loveable Scottish Boys member Hughie is still having relationship problems with former superheroine Starlight, more normally referred to as Annie. Vought-American is still up to lots of things, most of them profitable and dreadful. But with armageddon averted, Boys leader Bill Butcher suggests that the Boys take a vacation.

But when a Russian superhero ally of the Boys shows up dead along with a black marketeer, the vacation is cut short. And then the deaths of both supporting and main characters start to mount. Who is tidying up? Was the superhero coup the real threat? Is Hughie capable, mentally and physically, of engaging this newly revealed conspiracy and saving millions or perhaps even billions of lives? Is this Garth Ennis' last superhero comic book? All will be revealed. Highly recommended.

Wednesday, January 9, 2013

Minotaur

The Cabin in the Woods: written by Joss Whedon and Drew Goddard; directed by Drew Goddard; starring Kristen Connolly (Dana), Chris Hemsworth (Curt), Anna Hutchison (Jules), Fran Kranz (Marty), Jesse Williams (Holden), Richard Jenkins (Sitterson), Bradley Whitford (Hadley), and Sigourney Weaver (The Director) (2011): In a perfect world, The Cabin in the Woods would, at the very least, get a Best Original Screenplay Oscar nomination for 2012. But it's a horror movie and it's a comedy, so it won't. Nonetheless, it is a humdinger.

Joss Whedon and Drew Goddard, who worked together on Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Angel, conjure up something special here: a postmodern, metafictional slasher movie that also works as a nifty addition to the Cthulhu Mythos and as a commentary on the tastes of both horror audiences and horror-film makers. Light-footed and well-acted, it never becomes leaden and it never punches the audience in the face with its cleverness. It's a Charlie Kaufman film without the underlying pomposity.

Five college students on Spring Break go to a cabin in the woods. And then...well, frankly, you should experience it yourself. The ads and trailers for the movie gave way too much away as it is. Like the Scream movies, The Cabin in the Woods plays with cliches of the modern horror film. Unlike the Scream movies, it never becomes what it parodies. As one character realizes, "We are not who we are."

If nothing else, this may be the first horror movie that could be read as a metaphor for U.S. drone strikes on targets in Pakistan. Or I may be overthinking it. But you'll never look at a bank of elevators the same way again. Or a Japanese horror movie. Highly recommended.

Joss Whedon and Drew Goddard, who worked together on Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Angel, conjure up something special here: a postmodern, metafictional slasher movie that also works as a nifty addition to the Cthulhu Mythos and as a commentary on the tastes of both horror audiences and horror-film makers. Light-footed and well-acted, it never becomes leaden and it never punches the audience in the face with its cleverness. It's a Charlie Kaufman film without the underlying pomposity.

Five college students on Spring Break go to a cabin in the woods. And then...well, frankly, you should experience it yourself. The ads and trailers for the movie gave way too much away as it is. Like the Scream movies, The Cabin in the Woods plays with cliches of the modern horror film. Unlike the Scream movies, it never becomes what it parodies. As one character realizes, "We are not who we are."

If nothing else, this may be the first horror movie that could be read as a metaphor for U.S. drone strikes on targets in Pakistan. Or I may be overthinking it. But you'll never look at a bank of elevators the same way again. Or a Japanese horror movie. Highly recommended.

Tuesday, January 8, 2013

After the Superman

After the Thin Man: written by Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett, based on a story by Dashiell Hammett; directed by W.S. Van Dyke; starring William Powell (Nick Charles), Myrna Loy (Nora Charles), James Stewart (David Graham), Elissa Landi (Selma Landis) and Joseph Calleia (Dancer) (1936): Frothy second movie in the classic Thin Man franchise is uncharacteristically long for its era (113 minutes!) and in need of a trim of about 20 of those minutes, pretty much all from the beginning. Perpetually drunk Nick and Nora Charles return to San Francisco after a New York vacation to find another murder to solve with the occasional help/hindrance of dog Asta and the police.

Unfortunately, the film takes its own sweet time getting to that murder, and there's only so many party sequences one can watch. Witty bon mots and double-takes and double-entendres result, along with Jimmy Stewart as the second lead, a love-lorn bachelor. Eventually a murder occurs for Nick and Nora to solve. Also much shouting. Still, diverting fun. Recommended.

Superman vs. The Elite: written by Joe Kelly, based on his 2001 comic-book story "What So Funny 'Bout Truth, Justice, and the American Way?"; directed by Michael Chang; starring the voices of George Newbern (Superman), Pauley Perrette (Lois Lane), Robin Atkin Downes (Manchester Black) and Dee Bradley Baker (Atomic Skull) (2012): One of DC/Warner's periodic attempts to make their superheroes look like anime characters. Joe Kelly, with what I'd assume is some editorial direction from up the food chain, somewhat mucks up his excellent early-oughts Superman comic-book story "What So Funny 'Bout Truth, Justice, and the American Way?". That story was a response to the ultraviolent superheroes of the time, specifically Wildstorm's The Authority.

Here, Superman is made to look like something of a moralizing twit by the reduction in the Elite's tendency to create collateral damage among innocent bystanders. Their designs on world governance remain pretty much the same, but the movie also delves into the back-story of team-leader Manchester Black, making him more sympathetic and making the team as a whole less irresponsible and less power-hungry.

It doesn't help that a sub-plot sees Superman-villain-B-lister the Atomic Skull escape from jail twice and kill dozens of innocent bystanders. Somewhere, the concrete reasons for why one wouldn't want super-powered vigilantes running around killing people gets lost in translation. And why do cities persist in jailing supervillains so close to their downtown cores? The anime style isn't particularly compelling, occasionally making Superman look more like one of the Ripping Friends. Lightly recommended, but you'd be better off reading the comic book instead.

Unfortunately, the film takes its own sweet time getting to that murder, and there's only so many party sequences one can watch. Witty bon mots and double-takes and double-entendres result, along with Jimmy Stewart as the second lead, a love-lorn bachelor. Eventually a murder occurs for Nick and Nora to solve. Also much shouting. Still, diverting fun. Recommended.

Superman vs. The Elite: written by Joe Kelly, based on his 2001 comic-book story "What So Funny 'Bout Truth, Justice, and the American Way?"; directed by Michael Chang; starring the voices of George Newbern (Superman), Pauley Perrette (Lois Lane), Robin Atkin Downes (Manchester Black) and Dee Bradley Baker (Atomic Skull) (2012): One of DC/Warner's periodic attempts to make their superheroes look like anime characters. Joe Kelly, with what I'd assume is some editorial direction from up the food chain, somewhat mucks up his excellent early-oughts Superman comic-book story "What So Funny 'Bout Truth, Justice, and the American Way?". That story was a response to the ultraviolent superheroes of the time, specifically Wildstorm's The Authority.

Here, Superman is made to look like something of a moralizing twit by the reduction in the Elite's tendency to create collateral damage among innocent bystanders. Their designs on world governance remain pretty much the same, but the movie also delves into the back-story of team-leader Manchester Black, making him more sympathetic and making the team as a whole less irresponsible and less power-hungry.

It doesn't help that a sub-plot sees Superman-villain-B-lister the Atomic Skull escape from jail twice and kill dozens of innocent bystanders. Somewhere, the concrete reasons for why one wouldn't want super-powered vigilantes running around killing people gets lost in translation. And why do cities persist in jailing supervillains so close to their downtown cores? The anime style isn't particularly compelling, occasionally making Superman look more like one of the Ripping Friends. Lightly recommended, but you'd be better off reading the comic book instead.

Walk Like a Giant

Crumb: directed by Terry Zwigoff; starring Robert Crumb, Aline Kominsky, Charles Crumb, and Max Crumb (1994): Zwigoff's labour-of-love documentary, filmed over the course of nearly a decade, lays bare some of the tortured family and personal history of the great American writer-artist Robert Crumb. It also dwells too much upon the psychosexual aspects of Crumb's artistic output, leaving about 90% of his body of work underexplored.

I can see why this happens -- the psychosexual stuff is definitely the most provocative work for an audience that may not know Crumb or his output. Though they might have sat still for half-an-hour of Crumb's in-depth musings on music, 'authentic' culture, pop culture, or psychoanalysis. I guess we'll never know.

Crumb's interactions with his two brothers form the core of the movie's (unspoken) thesis -- that Crumb's ability to write and draw, and more importantly his ability to get that artistic output into the public eye, saved him from a life of psychological horror and isolated squalor. His two brothers are tragic wrecks -- highly intelligent, idiosyncratic artists themselves, and utterly damned by some combination of nature and nurture to lead secluded lives of quiet desperation. They are, quite simply, Robert Crumb as through a glass darkly.

Meanwhile, Crumb bops along, sometimes tortured himself but perpetually in motion, perpetually drawing (some of the most riveting scenes in the documentary simply show Crumb drawing -- and boy, is he fast and precise when he wants to be! His dialogue with his son comes across as a quick explanation of how an experienced cartoonist 'cheats' in order to create a specific effect, and should probably be required viewing for anyone with serious designs on being an artist).

Present and former girlfriends and wives show up to interact with Crumb and to delve into their relationships with him. Critics praise his work, or condemn it as being hateful of women and thus potentially dangerous (this was the height of McKinnon/Dworkin group-think about how pornography was in and of itself rape, as indeed were all heterosexual sex acts regardless of consent, because all male/female sex is rape...good times!).

Crumb himself comes across as seemingly disingenuous about the content of some of his work until one realizes that he simply can't afford the luxury of self-editing because people may get offended -- as he says at one point, if he doesn't draw and write out his thoughts, he starts to go crazy. In some cases, what's on the page seems to be spewed forth directly from his Id. Is it offensive? Oh, yeah, sometimes.

Is it Art? Oh, yeah -- the greatest body of work of any American writer-artist, ever. I'm not even sure if anyone is even close to Crumb's body of work and the now-fifty-year-long level of achievement therein. The gap between him and everyone else in his field in the United States is as great as the gap between Shakespeare and everyone else in English literature. Maybe greater. And all of it done singing out of darkness. Highly recommended.

I can see why this happens -- the psychosexual stuff is definitely the most provocative work for an audience that may not know Crumb or his output. Though they might have sat still for half-an-hour of Crumb's in-depth musings on music, 'authentic' culture, pop culture, or psychoanalysis. I guess we'll never know.

Crumb's interactions with his two brothers form the core of the movie's (unspoken) thesis -- that Crumb's ability to write and draw, and more importantly his ability to get that artistic output into the public eye, saved him from a life of psychological horror and isolated squalor. His two brothers are tragic wrecks -- highly intelligent, idiosyncratic artists themselves, and utterly damned by some combination of nature and nurture to lead secluded lives of quiet desperation. They are, quite simply, Robert Crumb as through a glass darkly.

Meanwhile, Crumb bops along, sometimes tortured himself but perpetually in motion, perpetually drawing (some of the most riveting scenes in the documentary simply show Crumb drawing -- and boy, is he fast and precise when he wants to be! His dialogue with his son comes across as a quick explanation of how an experienced cartoonist 'cheats' in order to create a specific effect, and should probably be required viewing for anyone with serious designs on being an artist).

Present and former girlfriends and wives show up to interact with Crumb and to delve into their relationships with him. Critics praise his work, or condemn it as being hateful of women and thus potentially dangerous (this was the height of McKinnon/Dworkin group-think about how pornography was in and of itself rape, as indeed were all heterosexual sex acts regardless of consent, because all male/female sex is rape...good times!).

Crumb himself comes across as seemingly disingenuous about the content of some of his work until one realizes that he simply can't afford the luxury of self-editing because people may get offended -- as he says at one point, if he doesn't draw and write out his thoughts, he starts to go crazy. In some cases, what's on the page seems to be spewed forth directly from his Id. Is it offensive? Oh, yeah, sometimes.

Is it Art? Oh, yeah -- the greatest body of work of any American writer-artist, ever. I'm not even sure if anyone is even close to Crumb's body of work and the now-fifty-year-long level of achievement therein. The gap between him and everyone else in his field in the United States is as great as the gap between Shakespeare and everyone else in English literature. Maybe greater. And all of it done singing out of darkness. Highly recommended.

Sunday, January 6, 2013

Kirby Power

So far as I understand it, the goal here was to introduce pretty much every character in the Kirbyverse in one epic miniseries. Mission accomplished. Early on, it feels a bit like a roll call (or maybe a role call). As the story progresses, Busiek's strengths as a humanistic chronicler of superheroes get a chance to breathe, though the story nonetheless adheres to the kitchen-sink approach of some of Kirby's later books: characters and concepts pile up on the page. This is the opposite of decompressed storytelling.

The mesh of Jack Herbert and Alec Ross's art works pretty well for the most part, with Herbert supplying the more traditional pen-and-ink drawing and Ross (and his painted, hyper-realistic art) moving in and out of the narrative with full-and-double-page spreads for the really epic moments. Many of Kirby's tropes are here, from space-gods to misunderstood monsters, along with character designs from a never-implemented reimagining of Marvel's (and Kirby's) Thor that are really something to see in action. Recommended.

Labels:

alex ross,

captain victory,

jack kirby,

kirby genesis,

kurt busiek,

silver star,

tiger 6

Altered States

Freed from 'normal' continuity, Robinson really goes all out here -- this is DC's best superhero book right now. Nicola and Trevor Scott supply clean, vaguely retro artwork (in the sense that it's not overcrowded and doesn't rely on the computerized colour palette for most of its best effects). The 'new' versions of old heroes are a pretty interesting lot, as Robinson seems to have been given carte blanche to rework the origins of the heroes. The Flash is now a magical hero, his super-speed granted by a dying Mercury (yes, that Mercury); the Green Lantern now fills Swamp Thing's role as a guardian of the world's biosphere. Oh, and Sandman is Canadian.

In the world of Earth-2, the Big Three -- Superman, Wonder Woman, and Batman -- died in a last-ditch (and successful) effort to save Earth from a global invasion by the malign, super-powered forces of the planet Apokolips. Years later, with the Earth rebuilding, the next wave of heroes finally starts to emerge: the Flash, Green Lantern, Hawkgirl, the Atom, the Sandman, and soon all the other Golden-Age heroes, I'm assuming.

But a second invasion from Apokolips may be looming. And on the homefront, Mr. 8 (Mister Terrific in the Golden-Age continuity) advances his plans to save the Earth by any means necessary, which in the past resulted in the deaths of tens of millions of humans during the Apokolips War.

It's all a lot of occasionally grim but mostly surprising super-hero fun. Robinson seems to have been rejuvenated himself by getting to work on an alternate continuity; here's hoping he gets to write this for a few years, and that editorial interference stays at a minimum. Recommended.

Saturday, January 5, 2013

Earth's Greatest Hero

Here, we get the origin of Tom Strong, raised from birth to be the world's greatest physical and mental specimen. We also get some adventures circa 2000 fighting super-Nazis and giant, intelligent slime molds and self-replicating super-machines, and flashback stories detailing Strong's back-story from the 1920's, 1940's, and 1950's. The present-day stuff is beautifully rendered by Chris Sprouse and Al Gordon, while the flashbacks contain crackerjack, period-appropriate (Tom's adventures span 100 years and about 100 genres) artwork by others. Highly recommended.

Tom Strong Volume 2: written by Alan Moore; illustrated by Chris Sprouse, Alan Gordon, Alan Weiss, Paul Chadwick, Gary Gianni, Kyle Baker, Pete Poplaski, Russ Heath, and Hilary Barta (2000-2001): The highlights of this second volume of Tom Strong adventures are a two-issue visit to Terra Obscura, Earth's alien-occupied twin, and the battle in The Tower at Time's End. The former is a loving nod to decades of crossover team-ups between super-heroes of different Earths. The latter is an in-depth homage to a class Captain Marvel Family adventure of the 1940's, complete with a C.C. Beck art tribute by Pete Poplaski that's a delight. Highly recommended.

Tom Strong Volume 3: written by Alan Moore and Leah Moore; illustrated by Chris Sprouse, Karl Story, Howard Chaykin, Shawn McManus, and Steve Mitchell (2002-2003): Much of the action here is taken up by Tom Strong, his family, and assorted allies battling an invasion of giant, space-faring ants. It's fun. Recommended.

Tom Strong Volume 4: written by Alan Moore, Peter Hogan, and Geoff Johns; illustrated by Chris Sprouse, Karl Story, Jerry Ordway, Trevor Scott. Sandra Hope, Richard Friend, John Dell, and John Paul Leon (2003-2004): Tom Strong gets to see his own life through the looking glass when a mysterious invader of the Stronghold HQ tells him the story of an alternate Earth's Tom Stone, who initially seems to have been a much better version of Tom Strong. But things change. Recommended.

Tom Strong Volume 5: written by Mark Schultz, Steve Aylett, Brian K. Vaughan, and Ed Brubaker; illustrated by Pasqual Ferry, Shawn McManus, Peter Snejberg, and Duncan Fegredo (2004): The only volume without any actual writing by Alan Moore, this one ends on a great two-parter that works as an homage to Moore's own work, specifically Miracleman/Marvelman, by Ed Brubaker and Duncan Fegredo. Recommended.

Tom Strong Volume 6: written by Michael Moorcock, Joe Casey, Steve Moore, Peter Hogan, and Alan Moore; illustrated by Chris Sprouse, Karl Story, Paul Gulacy, Jimmy Pamiotti, Ben Oliver, and Jerry Ordway (2005-2006): Thanks to DC's acquistion of Wildstorm, the former Image Comics imprint that was producing Tom Strong and the other titles in Moore's America's Best Comics line (Top Ten and Promethea chief among them), Tom Strong comes to a somewhat abrupt end as Moore pulls the plug rather than work for DC any longer, even at one remove (DC acquired Wildstorm near the beginning of Moore's ABC Comics line and The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen).

The legendary Michael Moorcock scripts a two-parter in which Tom and friends cross over with some Moorcock characters (and one extremely familiar looking black sword), while Moore himself writes the final issue, a crossover with the apocalyptic ending of Moore's Promethea series. Highly recommended.

Labels:

alan moore,

chris sprouse,

dave gibbons,

doc savage,

michael moorcock,

superman,

tarzan,

tom strong,

top ten

Thursday, January 3, 2013

When Super-powers Happen to Terrible People

The Boys Volume 3: Good for the Soul: written by Garth Ennis; illustrated by Darick Robertson (2008): Many terrible things happen and more terrible things are revealed about the superheroes of the world of The Boys. Pretty much all of them are corporate lackeys of Vought-American, a multi-national that's excellent at making money and terrible at making weapons that actually work.

Ennis and Robertson illustrate this with some World War Two references to profit-motivated cock-ups by arms manufacturers on the Allied side, all of which made the companies tons of money and all of which resulted in increased fatalities. Because modern warfare is all about money. The troops are essentially irrelevant except as testing units for the hardware, regardless of whether it's an improvement on the last hardware.

The super-powered Boys, funded by the CIA but running their own deeper game, once again take the piss out of some superheroes while trying to uncover the truth about 9/11 in their universe, where the Brooklyn Bridge and not the World Trade Center Towers was destroyed. A pretty searing portrait of dangerous, profit-motivated incompetence. Recommended.

The Boys Volume 6: The Self-Preservation Society: written by Garth Ennis; illustrated by Darick Robertson, John McCrea, and Carlos Ezquerra (2009-2010): Payback, Ennis's horrifying parody of Marvel's Avengers, comes after The Boys. Stormfront, Payback's thinly veiled version of Thor, is an actual Nazi used by uber-corporation Vought-American to exterminate undesireable ethnics on Third-World land they want to purchase when he's not posing for photo ops and pretending to be a German God of Thunder.

But like pretty much ever other super-powered character in Ennis's bleak vision of the world, he's never been properly trained in hand-to-hand combat because he's simply too powerful to worry about it. That's about to change. Another bracing, barbaric, ultraviolent yawp against the world's violent stupidities. Recommended.

John Byrne's Next Men: Scattered Part 2: written and illustrated by John Byrne (2010): Byrne's great 1990's series, once on a 15-year hiatus, draws to a (sorta) close, as one volume remains. The time-travel stuff is complicated but nicely reasoned out; the stakes are high; everything we saw long ago in the first issues moves satisfyingly towards an ending. But you'll need to read everything that came before to understand what comes now. Recommended.

John Byrne's Next Men: Scattered Part 2: written and illustrated by John Byrne (2010): Byrne's great 1990's series, once on a 15-year hiatus, draws to a (sorta) close, as one volume remains. The time-travel stuff is complicated but nicely reasoned out; the stakes are high; everything we saw long ago in the first issues moves satisfyingly towards an ending. But you'll need to read everything that came before to understand what comes now. Recommended.

Ennis and Robertson illustrate this with some World War Two references to profit-motivated cock-ups by arms manufacturers on the Allied side, all of which made the companies tons of money and all of which resulted in increased fatalities. Because modern warfare is all about money. The troops are essentially irrelevant except as testing units for the hardware, regardless of whether it's an improvement on the last hardware.

The super-powered Boys, funded by the CIA but running their own deeper game, once again take the piss out of some superheroes while trying to uncover the truth about 9/11 in their universe, where the Brooklyn Bridge and not the World Trade Center Towers was destroyed. A pretty searing portrait of dangerous, profit-motivated incompetence. Recommended.

The Boys Volume 6: The Self-Preservation Society: written by Garth Ennis; illustrated by Darick Robertson, John McCrea, and Carlos Ezquerra (2009-2010): Payback, Ennis's horrifying parody of Marvel's Avengers, comes after The Boys. Stormfront, Payback's thinly veiled version of Thor, is an actual Nazi used by uber-corporation Vought-American to exterminate undesireable ethnics on Third-World land they want to purchase when he's not posing for photo ops and pretending to be a German God of Thunder.

But like pretty much ever other super-powered character in Ennis's bleak vision of the world, he's never been properly trained in hand-to-hand combat because he's simply too powerful to worry about it. That's about to change. Another bracing, barbaric, ultraviolent yawp against the world's violent stupidities. Recommended.