The Thing from Another World: adapted by Charles Lederer, Howard Hawks, and Ben Hecht from the novella "Who Goes There?" by John Campbell Jr.; directed by Christian Nyby and Howard Hawks; starring Margaret Sheridan (Nikki), Kenneth Tobey (Captain Pat Hendry), Robert Cornthwaite (Dr. Carrington), Douglas Spencer (Scotty) and James Young (Lt. Eddie Dykes) (1951): I suppose it's a measure of the contempt the producers and writers had for the source material that almost nothing remains of that source novella except the temperature (it's still cold) and the general idea (crashed UFO with an angry survivor).

The Thing from Another World nonetheless remains one of the minor science-fiction classics of the 1950's, but it's amazing how much is changed from John Campbell's 1938 original: not even the original names of characters survive in the screenplay.

Anyway, a UFO crashes at the North Pole near a U.S. experimental base. Some Air Force guys, led by the wooden Kenneth Tobey, arrive to help investigate. Soon, an alien with remarkable recuperative powers and an unquenchable thirst for blood starts rampaging around the experimental station. As he's a giant carrot, shooting him does no good, and unlike later versions of The Thing, there aren't a lot of flamethrowers lying around the base.

The movie's quite tense, with the hulking, monosyllabic alien -- who turns out to look like a bald Frankenstein's monster in a jump-suit -- kept offscreen most of the time, possibly because he looks like a bald Frankenstein's monster in a jump-suit . Campbell's paean to the resourcefulness of civilian scientists and engineers here becomes a paean to the resourcefulness of the Air Force. The chief, Nobel-winning scientist is an idiot who keeps trying to make peace with the alien even as the human body count mounts.

Though Professor Quisling really does have a point -- who wouldn't be pissed after crashing on an alien planet, getting frozen in a block of ice, and then almost immediately getting one's arm ripped off by a sled dog when one awakes? This has to be the worst first-contact scenario ever. Especially since the Air Force accidentally blows up the guy's UFO with some thermite while trying to excavate it from the ice. I'll be damned if I know why there were in such a hurry, and I'd hate to see them at a major archaeological dig.

It's fun to chart the differences between this film and John Carpenter's later, much more faithful adaptation of Campbell's novella. Only the giant carrot is a justifiable change -- visual effects of the early 1950's weren't up to a shape-changing alien. Watch the skies! Recommended.

Friday, September 28, 2012

Wednesday, September 26, 2012

Land of Dreams

Sandman: The Dream Hunters: adapted by P. Craig Russell from a novella by Neil Gaiman and Yoshiaka Amano (2009): Writer-artist Russell adapted Neil Gaiman's illustrated 1999 Sandman novella into comic-book form to help celebrate the 20th anniversary of the first issue of Gaiman's hyper-popular Sandman series. The novella itself was released to celebrate the 10th anniversary of Sandman. What will the 30th anniversary bring?

Told as if it were an old Japanese folk story (it isn't, though Gaiman's afterword to the 1999 novella convinced a lot of people, including Russell, that it was), The Dream Hunters chronicles the adventures of a female fox, a young monk, and a magician searching for a cure for his chronic fear. It's set in a legendary Japan of animal spirits, demons, and witches. The Sandman himself -- Dream, or Morpheus -- plays a supporting role, as he periodically did in his own comic-book series. The narrative focus is squarely upon the fox and the monk.

Russell's art is pleasingly legendary in its own way, as sometimes cartoony and sometimes nightmarish demons rub shoulders with realistically rendered humans, a slightly anthropomorphic fox, and some truly horrible witches. Or are they oracles? Russell's faces are always expressive, that expressiveness the product of just a few lines properly placed.

The colouring by Lovern Kindzierski apparently tries to replicate the palette available to Japanese print-makers of a certain era. It's a lovely, muted wash of pastels and faded primary colours. Much of the wording remains Gaiman's, but Russell has done a fine job of selecting what to keep in language and what to render as art. All in all, this is a marvelous addition to the Sandman library, and worth owning whether or not one already has the novella. Highly recommended.

Told as if it were an old Japanese folk story (it isn't, though Gaiman's afterword to the 1999 novella convinced a lot of people, including Russell, that it was), The Dream Hunters chronicles the adventures of a female fox, a young monk, and a magician searching for a cure for his chronic fear. It's set in a legendary Japan of animal spirits, demons, and witches. The Sandman himself -- Dream, or Morpheus -- plays a supporting role, as he periodically did in his own comic-book series. The narrative focus is squarely upon the fox and the monk.

Russell's art is pleasingly legendary in its own way, as sometimes cartoony and sometimes nightmarish demons rub shoulders with realistically rendered humans, a slightly anthropomorphic fox, and some truly horrible witches. Or are they oracles? Russell's faces are always expressive, that expressiveness the product of just a few lines properly placed.

The colouring by Lovern Kindzierski apparently tries to replicate the palette available to Japanese print-makers of a certain era. It's a lovely, muted wash of pastels and faded primary colours. Much of the wording remains Gaiman's, but Russell has done a fine job of selecting what to keep in language and what to render as art. All in all, this is a marvelous addition to the Sandman library, and worth owning whether or not one already has the novella. Highly recommended.

Labels:

folklore,

foxes,

japan,

morpheus,

neil gaiman,

p. craig russell,

sandman,

the dream hunters,

vertigo

Sunday, September 23, 2012

Gorky Park 2: Gork Harder

Polar Star by Martin Cruz Smith (1989): Set in the waning days of the Soviet Union and the early days of glasnost and perestroika, Polar Star brings Smith's dogged investigator Arkady Renko back for another investigation no one really wants to succeed.

Stripped of his Party card and his status as a police officer after the events of Gorky Park (about six years before the beginning of this novel), Renko now works the "slime line" on a massive Soviet fish-processing ship, the Polar Star, currently working the Pacific fishing zones north of the Aleutian island chain.

But while gutting fish for a living has turned out to be a good way to numb Renko to his past, his past isn't done with him yet. A female crew member shows up dead in one of the nets. The Polar Star's cooperative venture with several American fishing trawlers makes the investigation more complex than it initially seems. And as Renko is the only man aboard with a background in police work, he's drafted by the Captain and the omnipresent Political Officer to investigate the death and, hopefully, rule it a suicide.

Set almost entirely on the Polar Star, the novel portrays in fascinating detail everything from the workings of industrial-size fishing boats to the crew's obsession with buying Western consumer goods during their one-day stopover in Dutch Harbour. We also get a brief tour through Soviet-era folk-singing, a twisty murder plot, and a brief exegesis on sub-hunting. Also, fish and fishing and the awful slime eels.

Renko is even more depressed and jaded than he was in Gorky Park, understandably so. But before it's all over, he'll have to resurrect the detective part of himself -- and, to some extent, the part of himself that actually wants to continue living. Highly recommended.

Stripped of his Party card and his status as a police officer after the events of Gorky Park (about six years before the beginning of this novel), Renko now works the "slime line" on a massive Soviet fish-processing ship, the Polar Star, currently working the Pacific fishing zones north of the Aleutian island chain.

But while gutting fish for a living has turned out to be a good way to numb Renko to his past, his past isn't done with him yet. A female crew member shows up dead in one of the nets. The Polar Star's cooperative venture with several American fishing trawlers makes the investigation more complex than it initially seems. And as Renko is the only man aboard with a background in police work, he's drafted by the Captain and the omnipresent Political Officer to investigate the death and, hopefully, rule it a suicide.

Set almost entirely on the Polar Star, the novel portrays in fascinating detail everything from the workings of industrial-size fishing boats to the crew's obsession with buying Western consumer goods during their one-day stopover in Dutch Harbour. We also get a brief tour through Soviet-era folk-singing, a twisty murder plot, and a brief exegesis on sub-hunting. Also, fish and fishing and the awful slime eels.

Renko is even more depressed and jaded than he was in Gorky Park, understandably so. But before it's all over, he'll have to resurrect the detective part of himself -- and, to some extent, the part of himself that actually wants to continue living. Highly recommended.

Gorky Park

Gorky Park by Martin Cruz Smith (1981): Smith's late-Cold-War thriller was a huge success in 1981, soon spawning a big-budget film adaptation starring William Hurt. It involves the efforts of Moscow homicide investigator Arkady Renko to somehow solve a triple homicide that ultimately almost no one -- not the Politburo, his superiors, or the KGB -- wants him to solve.

The novel's greatest strength is its accumulation of detail about the workings of Soviet society at the tail end of the Brehznev era. Regardless of how accurate the novel's details are, they seem accurate through their specificity and consistency and through Smith's wide-ranging depiction of everything from the philosophy of appliance-buying to the average citizen's reliance on vodka.

The middle-aged Renko is a sharply drawn character in the world-weary but noble tradition of hard-boiled detectives, and his outsider-status in his own department almost makes him a private detective rather than a cop. Burdened by family history (his mother committed suicide while his still-living father is an unrepentant former general with Stalinist leanings), Renko nonetheless doggedly pursues the truth in a situation where no one really wants to know the truth.

As a depiction of a decaying totalitarian system, Gorky Park is excellent -- the Soviet bureaucracy is a blighted wonder to behold. But the novel also takes the worst aspects of the United States to task as it winds its labyrinthine way through a conspiracy that's both much more and much less than it appears to be. Highly recommended.

Labels:

arkady renko,

brezhnev,

gorky park,

martin cruz smith,

renko,

soviet,

ussr

Saturday, September 22, 2012

Bat-Time

Time and the Batman: written by Grant Morrison and Fabian Nicienza; illustrated by Frank Quitely, David Finch, Tony Daniel, and others (2010): Collecting Batman 700-703, this collection could also have been titled 'Loose Ends', as it comprises one double-length anniversary story, two 'missing' chapters from the previous Batman R.I.P. storyline ('missing' in the sense that Morrison could only tell them after that story was over, as they gave away certain plot points), and a bridge issue leading into The Return of Bruce Wayne.

The art is top-notch throughout, and Morrison gets his loopy on with the 700th anniversary story, which spans hundreds of thousands of years and features several different Batmen (Batmans?) in several different time periods, though the three lengthiest stories focus on Bruce Wayne, Dick Grayson, and Damian Wayne.

Morrison pulls in one of the Silver Age Batman's weirdest story ideas -- a time machine that essentially hypnotizes people into different eras (!) -- as a prelude to The Return of Bruce Wayne, the Batman time-travel story to end all Batman time-travel stories. Well, until the next one anyway.

Enjoyable but short (about 120 pages, padded with pin-ups and diagrams of the Bat-Cave), this is best enjoyed by completists or by people who find it remaindered, as I did. As a hardcover, it's worth $10-$12, but not the original +$20 cover price. Recommended.

The art is top-notch throughout, and Morrison gets his loopy on with the 700th anniversary story, which spans hundreds of thousands of years and features several different Batmen (Batmans?) in several different time periods, though the three lengthiest stories focus on Bruce Wayne, Dick Grayson, and Damian Wayne.

Morrison pulls in one of the Silver Age Batman's weirdest story ideas -- a time machine that essentially hypnotizes people into different eras (!) -- as a prelude to The Return of Bruce Wayne, the Batman time-travel story to end all Batman time-travel stories. Well, until the next one anyway.

Enjoyable but short (about 120 pages, padded with pin-ups and diagrams of the Bat-Cave), this is best enjoyed by completists or by people who find it remaindered, as I did. As a hardcover, it's worth $10-$12, but not the original +$20 cover price. Recommended.

Nefandous

H.P. Lovecraft: Tales: edited by Peter Straub (Collected 2005): If you're going to buy one collection of H.P. Lovecraft's horror and science-fiction stories, this Library of America volume is the one. While it omits the products of about ten years of HPL's apprenticeship learning to write, along with all of his Dunsany-era stories, it nonetheless does contain pretty much all of Lovecraft's essential fiction. The inclusion of his essay on supernatural fiction would have been nice, but the appendices make up for that exclusion.

More importantly, Straub uses the new standard HPL texts as assembled by S.T. Joshi from Lovecraft's original manuscripts and the original magazine appearances of these stories. As monumentally important as editor and publisher August Derleth was to the survival and posthumous propagation of Lovecraft's work, his editing instincts were always somewhat wonky. Derleth tended to think that italicizing key passages and putting exclamation marks after every third sentence made HPL scarier! It didn't. The much calmer, less obtrusive prose of these remastered stories restores a lot of the lost grandeur and sublimity of Lovecraft's greatest moments.

While Lovecraft made cosmic horror and imaginary gods a staple of American horror fiction forever after, he also made the documentary tone a mainstay of horror fiction. Most stories are first-person accounts given by a narrator who has survived the events (at least for a little while -- there's always a cost to saving the Earth) or who has collected information about events that he himself did not participate in. One of the odd things about the current horror boom in 'found-footage' and 'fake documentary' films is that HPL would have loved them: they, and not narrative horror, are the closest approximation on the screen of what the narration of stories from his mature writing period seeks to achieve.

As other critics have noted, one of the fascinating things about looking at HPL's stories in the order of composition rather than the order of publication is to see him gradually losing interest in horror. His work after 1931 or so (he died in 1937 at the age of 47) moves more and more towards being straight, though extravagantly cosmic, science fiction in which all the mythological elements have rational (albeit bizarre) explanations.

For example, the cosmic aliens of "The Whisperer in Darkness" and "The Shadow Out of Time" really aren't that menacing -- certainly not compared to the invading horrors in the earlier "The Call of Cthulhu" or "The Colour Out of Space." Indeed, the time-travelling Great Race of "The Shadow Out of Time" turns out to be relatively benign, while the Mi-Go of "Whisperer" seem more misunderstood nuisance than threat.

Another progression involves Lovecraft's oft-mentioned racism and bigotry. In his early 1920's story "The Horror at Red Hook", pretty much all the horror flows out of Lovecraft's then-deep-seated loathing of non-WASPy ethnic types, African-Americans, Asian-Americans, and miscegenation. But by the last two chronological stories in this collection, Lovecraft presents Australian aboriginals as the only group with a rational response to the things that lurk in the cyclopean ruins of ancient cities hidden in the Outback, and working-class Italian Americans as the last line of defense against the resurrection of the extraordinarily dangerous Nyarlathotep. It's a welcome shift in attitude.

In any event, this is a fine collection with a decent bibliography, time-line, and annotations, though the last seems a bit scanty. Though it at least defines the word 'nefandous.' Highly recommended.

More importantly, Straub uses the new standard HPL texts as assembled by S.T. Joshi from Lovecraft's original manuscripts and the original magazine appearances of these stories. As monumentally important as editor and publisher August Derleth was to the survival and posthumous propagation of Lovecraft's work, his editing instincts were always somewhat wonky. Derleth tended to think that italicizing key passages and putting exclamation marks after every third sentence made HPL scarier! It didn't. The much calmer, less obtrusive prose of these remastered stories restores a lot of the lost grandeur and sublimity of Lovecraft's greatest moments.

While Lovecraft made cosmic horror and imaginary gods a staple of American horror fiction forever after, he also made the documentary tone a mainstay of horror fiction. Most stories are first-person accounts given by a narrator who has survived the events (at least for a little while -- there's always a cost to saving the Earth) or who has collected information about events that he himself did not participate in. One of the odd things about the current horror boom in 'found-footage' and 'fake documentary' films is that HPL would have loved them: they, and not narrative horror, are the closest approximation on the screen of what the narration of stories from his mature writing period seeks to achieve.

As other critics have noted, one of the fascinating things about looking at HPL's stories in the order of composition rather than the order of publication is to see him gradually losing interest in horror. His work after 1931 or so (he died in 1937 at the age of 47) moves more and more towards being straight, though extravagantly cosmic, science fiction in which all the mythological elements have rational (albeit bizarre) explanations.

For example, the cosmic aliens of "The Whisperer in Darkness" and "The Shadow Out of Time" really aren't that menacing -- certainly not compared to the invading horrors in the earlier "The Call of Cthulhu" or "The Colour Out of Space." Indeed, the time-travelling Great Race of "The Shadow Out of Time" turns out to be relatively benign, while the Mi-Go of "Whisperer" seem more misunderstood nuisance than threat.

Another progression involves Lovecraft's oft-mentioned racism and bigotry. In his early 1920's story "The Horror at Red Hook", pretty much all the horror flows out of Lovecraft's then-deep-seated loathing of non-WASPy ethnic types, African-Americans, Asian-Americans, and miscegenation. But by the last two chronological stories in this collection, Lovecraft presents Australian aboriginals as the only group with a rational response to the things that lurk in the cyclopean ruins of ancient cities hidden in the Outback, and working-class Italian Americans as the last line of defense against the resurrection of the extraordinarily dangerous Nyarlathotep. It's a welcome shift in attitude.

In any event, this is a fine collection with a decent bibliography, time-line, and annotations, though the last seems a bit scanty. Though it at least defines the word 'nefandous.' Highly recommended.

Thursday, September 20, 2012

Mirror Phase

The Lady from Shanghai: adapted by Orson Welles, William Castle, Charles Lederer, and Fletcher Markle from the novel If I Die Before I Wake by Sherwood King; directed by Orson Welles; starring Orson Welles (Michael O'Hara), Rita Hayworth (Elsa Bannister), Everett Sloane (Arthur Bannister), and Glenn Anders (George Grisby) (1947): Welles wrote, directed, and starred in this movie so as to secure $55,000 to mount a Mercury Theatre stage production of Around the World in 80 Days. Somewhere in the making of it, he seems to have decided to out-Hitchcock Hitchcock. And in many ways he succeeds, though I have a feeling that the original Director's Cut of 155 minutes (this version runs 87 minutes, which is just about right and maybe even a bit long) was probably unbearable.

Welles adopts a generic Irish accent for this movie, a decision that mostly eliminates his trademark baritone delivery. He's an itinerant sailor named Michael O'Hara who gets mixed up in the affairs of criminal-defense lawyer Arthur Bannister, eponymous trophy wife Elsa Bannister, and Bannister's weaselly partner George Grisby.

Some of Welles's choices for how the actors play their parts would later arise in Touch of Evil. Grisby and Arthur Bannister are both constructed around annoying tics, stagey business with Bannister's crutches, and in Grisby's case an astonishingly annoying manner of speech. The weirdness of these grotesque touches seems to foreshadow the work of the Coen Brothers and David Lynch, two directors who seem much more Wellesian to me than they're generally given credit for.

The plot contains many Hitchcockian tropes -- the innocent man accused of a crime, a luminous blonde love interest (Hayworth, her trademark long hair shorn for this picture), exotic or unusual locations, and odd yet compelling staging of key scenes. A love scene in an aquarium and the concluding shoot-out in a Hall of Mirrors are the most famous setpieces in The Lady from Shanghai, the latter much imitated in later films and television programs. I don't think this is a great film, but it's darned peculiar and interesting, and seems much more modern than many other films of the same era. Highly recommended.

Welles adopts a generic Irish accent for this movie, a decision that mostly eliminates his trademark baritone delivery. He's an itinerant sailor named Michael O'Hara who gets mixed up in the affairs of criminal-defense lawyer Arthur Bannister, eponymous trophy wife Elsa Bannister, and Bannister's weaselly partner George Grisby.

Some of Welles's choices for how the actors play their parts would later arise in Touch of Evil. Grisby and Arthur Bannister are both constructed around annoying tics, stagey business with Bannister's crutches, and in Grisby's case an astonishingly annoying manner of speech. The weirdness of these grotesque touches seems to foreshadow the work of the Coen Brothers and David Lynch, two directors who seem much more Wellesian to me than they're generally given credit for.

The plot contains many Hitchcockian tropes -- the innocent man accused of a crime, a luminous blonde love interest (Hayworth, her trademark long hair shorn for this picture), exotic or unusual locations, and odd yet compelling staging of key scenes. A love scene in an aquarium and the concluding shoot-out in a Hall of Mirrors are the most famous setpieces in The Lady from Shanghai, the latter much imitated in later films and television programs. I don't think this is a great film, but it's darned peculiar and interesting, and seems much more modern than many other films of the same era. Highly recommended.

Wednesday, September 19, 2012

A Distinct Lack of Meteor Residue

Apollo 18: written by Brian Miller; directed by Gonzalo Lopez-Gallego; starring Warren Christie (Ben Anderson), Lloyd Owen (Nate Walker) and Ryan Robbins (John Grey) (2011): Had the producers not done this film as 'found footage,' they'd have basically remade the Bruce Campbell/Walter Koenig classic Moon Trap. Well, sort of.

A secret Apollo mission blasts off into outer space at Christmas 1972 to ostensibly set up special cameras and monitoring devices at the Moon's South Pole. This is quite remarkable as the Saturn V rocket didn't carry enough fuel to get the standard three-man, two-vehicle Apollo mission to the Moon's South Pole, but so it goes.

The astronauts aren't told why they're really there, even though there's no reason not to brief them once they've discovered that things at the South Pole are a little wacky. Or perhaps even before, given that the Department of Defense -- which has ordered the secret mission -- seems to know an awful lot about what the astronauts are going to find soon after they land.

If ever a lunar mission needed that machine-gun-equipped rover from Armageddon (and some of the nuclear warheads from the same film), this would be that mission.

Found-footage shenanigans ensue, some of them pretty unlikely. Thankfully, the jamming of the astronauts' transmissions once they land on the Moon doesn't affect their crystal-clear video feed all the way back to Mission Control. Whatever. There's no time-lag in conversations between the astronauts and Mission Control, so maybe the whole thing was filmed on a sound stage in Burbank.

If your TV screen is big enough, you may get motion sickness from some of the camera work. And you'll never look at an innocent rock the same again. At 45 minutes or so, this might have made a good Outer Limits episode, but at 85 minutes it's interminable. Not recommended.

A secret Apollo mission blasts off into outer space at Christmas 1972 to ostensibly set up special cameras and monitoring devices at the Moon's South Pole. This is quite remarkable as the Saturn V rocket didn't carry enough fuel to get the standard three-man, two-vehicle Apollo mission to the Moon's South Pole, but so it goes.

The astronauts aren't told why they're really there, even though there's no reason not to brief them once they've discovered that things at the South Pole are a little wacky. Or perhaps even before, given that the Department of Defense -- which has ordered the secret mission -- seems to know an awful lot about what the astronauts are going to find soon after they land.

If ever a lunar mission needed that machine-gun-equipped rover from Armageddon (and some of the nuclear warheads from the same film), this would be that mission.

Found-footage shenanigans ensue, some of them pretty unlikely. Thankfully, the jamming of the astronauts' transmissions once they land on the Moon doesn't affect their crystal-clear video feed all the way back to Mission Control. Whatever. There's no time-lag in conversations between the astronauts and Mission Control, so maybe the whole thing was filmed on a sound stage in Burbank.

If your TV screen is big enough, you may get motion sickness from some of the camera work. And you'll never look at an innocent rock the same again. At 45 minutes or so, this might have made a good Outer Limits episode, but at 85 minutes it's interminable. Not recommended.

Labels:

apollo 18,

found footage,

mission control,

moon rocks,

nasa,

rocks,

spiders

Tuesday, September 18, 2012

Strange Spiders

Spider-man/Dr. Strange: Fever: written and illustrated by Brendan McCarthy with an additional story written by Stan Lee and Steve Ditko and illustrated by Steve Ditko (2010/1965; collected 2010): Enjoyable, wonky, slight and psychedelic team-up of Marvel's two biggest heroes co-created by the occasionally trippy pen of Steve Ditko.

That Ditko was amazingly good at conjuring up the weird magical vistas of sorcerer Dr. Strange always seemed a bit paradoxical, as Ditko's other strength lay in making his characters look realistically proportioned -- and New York realistically lived-in. Nonetheless, Ditko made magic look somehow effortless and cool and disquietingly surreal, and forty years of other Dr. Strange artists have struggled to approach the surreal-yet-grounded vistas and creatures of Ditko's realms of magic and mystery.

McCarthy has earned a name as a somewhat surreal comic-book artist, often more for his cover painting for books like Shade, The Changing Man (itself a revival of a trippy 1970's Ditko creation for DC Comics). Here, he grounds his magical dimensions in Australian aboriginal art, among other things, in this tale of Dr. Strange and Spider-man fighting spider-demons in another dimension.

McCarthy wisely keeps Strange and Spider-man believably human-proportioned and muscled, and some of the effects he achieves are quite lovely and strange. He's no Ditko, as the bonus reprint of the first Ditko-plotted-and-drawn Spider-man/Dr. Strange team-up shows, but he's definitely not your average 21st-century comic-book artist. Recommended.

Labels:

brendan mccarthy,

dr. strange,

fever,

spider-man,

steve ditko

Sunday, September 16, 2012

One Man Army Crap

OMAC: Omactivate!: written by Dan DiDio and Keith Giffen; illustrated by Keith Giffen, Scott Kolins, and Scott Koblish (2011-2012; collected 2012): One of the first cancelled series of DC's New 52, OMAC takes a quirky cult Jack Kirby character and turns him into a rather unpleasant Techno-Hulk. Keith Giffen is in full Kirby Kopy mode here, a style that's fun for a couple of issues but soon grows tiresome: the art looks like someone took late-period Kirby superhero art, squashed it, and then sanded all the edges off.

It doesn't help that the new character design for OMAC is terrifically ugly -- the original OMAC had a leaping Faux-hawk before we even knew such things existed; the new OMAC has a bristling, super-giant mane of a Faux-hawk that apparently works as an antenna for power beamed to him from outer space. It's both colossally ugly and sorta stupid.

The writing is worse than the art -- DiDio can only write characters who are either nebbishes or jerks. Creating sympathy isn't one of his strong suits. Lots of explosions and one- and two-page spreads put the focus on action, but it's action devoid of interest in those doing the action.

Originally, Kirby's 'OMAC' stood for 'One Man Army Corps.' That OMAC was a Techno-Shazam, complete with a non-powered secret identity with the initials 'BB' and powers that could come shooting out of the sky, not from a wizard's magic lightning but from a benign super-computer's satellite power generators.

Here, OMAC stands for 'One Machine Attack Construct.' Because that's way better than 'One Man Army Corps.' If you want to read an excellent, more modern riff on Kirby's 1970's character, seek out John Byrne's 4-issue OMAC miniseries from the early 1990's, a miniseries which manages to make its subject more 'realistic' while preserving the original concept in its entirety. This thing, though -- this thing sorta stinks. Not recommended.

Labels:

brother eye,

dan didio,

jack kirby,

keith giffen,

new 52,

omac,

one man army corps

Cake Walk

Layer Cake: adapted by J.J. Connolly from his novel; directed by Matthew Vaughn; starring Daniel Craig (unnamed protagonist), Tom Hardy (Clarkie), George Harris (Morty), Colm Meaney (Gene), Kenneth Cranham (Jimmy), Michael Gambon (Eddie Temple), Sienna Miller (Tammy), and Nathalie Lunghi (Charlie) (2004): Director Vaughn produced some of Guy Richie's films about the British underworld, and it shows in his directorial debut both in subject matter and style. This is a flashy, frothy picture that loves camera tricks and twisty plot developments.

Underneath the flash is a fairly simple story about a London cocaine producer (Craig) who gets sucked a lot further into his boss's schemes than he wanted. The McGuffin -- the boss asks Craig's unnamed protagonist to search for the missing daughter of a business colleague -- is dropped less than halfway through the film. Layer Cake has other things to do, most of them revolving around a huge shipment of ecstasy stolen from the Russian mob. Well, an Eastern European mob, in any case.

Crosses, double-crosses, and a little of the old ultraviolence ensue. Daniel Craig dresses up like a ninja in an assassination scene that pretty much destroys all suspension of disbelief. There is much screaming and beating in of heads and bullet holes in foreheads. Colm Meaney and Tom Hardy do what they can with their supporting roles, while Michael Gambon is the soul of high-level corruption.

Nonetheless, this is a fun movie if one has a high tolerance for graphic violence and under-developed characters. If it riffs unsuccessfully on Get Carter from time to time -- well, so it goes. Lightly recommended.

Underneath the flash is a fairly simple story about a London cocaine producer (Craig) who gets sucked a lot further into his boss's schemes than he wanted. The McGuffin -- the boss asks Craig's unnamed protagonist to search for the missing daughter of a business colleague -- is dropped less than halfway through the film. Layer Cake has other things to do, most of them revolving around a huge shipment of ecstasy stolen from the Russian mob. Well, an Eastern European mob, in any case.

Crosses, double-crosses, and a little of the old ultraviolence ensue. Daniel Craig dresses up like a ninja in an assassination scene that pretty much destroys all suspension of disbelief. There is much screaming and beating in of heads and bullet holes in foreheads. Colm Meaney and Tom Hardy do what they can with their supporting roles, while Michael Gambon is the soul of high-level corruption.

Nonetheless, this is a fun movie if one has a high tolerance for graphic violence and under-developed characters. If it riffs unsuccessfully on Get Carter from time to time -- well, so it goes. Lightly recommended.

Labels:

daniel craig,

get carter,

guy ritchie,

layer cake,

matthew vaughn

Hothouse

Inherit the Wind: screenplay by Nedrick Young and Harold Jacob Smith based on the play by Jerome Lawrence and Robert E. Lee; directed by Stanley Kramer; starring Spencer Tracy (Henry Drummond), Fredric March (Matthew Harrison Brady), Gene Kelly (E.K. Hornbeck), Dick York (Bertram T. Cates), Claude Akins (Reverend Jeremiah Brown), and Donna Anderson (Rachel Brown) (1960): As much about McCarthyism and the Red Scare as it is about the teaching of evolution in American schools, Inherit the Wind is loosely based on the Scopes 'Monkey Trial' of the 1920's. In that trial, the State of Tennessee prosecuted a substitute teacher for teaching evolution in a high-school biology class.

That set-up only partially remains here. The prosecuted high-school teacher in Inherit the Wind is full time and, to complicate things dramatically, engaged to the daughter of the preacher who has him brought up on charges in the first place. Yikes!

And as Dick York's schoolteacher lives in a small town, there's really nowhere for him to escape the growing mobs of angry, placard-waving, effigy-burning Christian fundamentalists except for the town jail, where he plays cards with the sympathetic, apologetic jailer.

In the real trial, famous American defense lawyer Clarence Darrow led a team of lawyers defending Scopes. The prosecution was led by former Presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan. Acerbically reporting on the whole affair was the famous H.L. Mencken.

Here, Matthew Harrison Brady stands in for Bryan, Henry Drummond stands in for Darrow, and Hornbeck stands in for Mencken. While the supporting roles are capably acted, and while Gene Kelly holds his own as the sarcastic, cynical Hornbeck, it's Fredric March and Spencer Tracy who command the stage here.

March is bombastic as the fiery, Bible-thumping Brady, while Tracy is slightly cooler and much funnier as the 'famous agnostic' Drummond. That the men share a history going back 40 years and were once friends adds another level to the intellectual conflict: both are disappointed in the path the other has taken, though only Drummond strives to cool things down, unsuccessfully, throughout the trial.

With more than an hour devoted to the courtroom proceedings -- many of them closely following the real arguments -- Inherit the Wind succeeds or fails on the basis of the drama of two men talking. I think it succeeds grandly, as these two old, titanic actors are given lines and scenes that allow for high drama centered around people talking, arguing, shouting, and occasionally mopping their brows in the steamy courtroom, in the steamy hotel, or on the steamy hotel porch. It's hot, dammit!

I imagine a lot of people would be turned off by a drama of ideas, especially one in which fundamentalist Christianity takes the intellectual and moral beating of a lifetime. I think it's swell, and in a way an obvious forerunner to the work of Aaron Sorkin, though here much of the talking is done while the characters remain mostly stationary. Highly recommended.

That set-up only partially remains here. The prosecuted high-school teacher in Inherit the Wind is full time and, to complicate things dramatically, engaged to the daughter of the preacher who has him brought up on charges in the first place. Yikes!

And as Dick York's schoolteacher lives in a small town, there's really nowhere for him to escape the growing mobs of angry, placard-waving, effigy-burning Christian fundamentalists except for the town jail, where he plays cards with the sympathetic, apologetic jailer.

In the real trial, famous American defense lawyer Clarence Darrow led a team of lawyers defending Scopes. The prosecution was led by former Presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan. Acerbically reporting on the whole affair was the famous H.L. Mencken.

Here, Matthew Harrison Brady stands in for Bryan, Henry Drummond stands in for Darrow, and Hornbeck stands in for Mencken. While the supporting roles are capably acted, and while Gene Kelly holds his own as the sarcastic, cynical Hornbeck, it's Fredric March and Spencer Tracy who command the stage here.

March is bombastic as the fiery, Bible-thumping Brady, while Tracy is slightly cooler and much funnier as the 'famous agnostic' Drummond. That the men share a history going back 40 years and were once friends adds another level to the intellectual conflict: both are disappointed in the path the other has taken, though only Drummond strives to cool things down, unsuccessfully, throughout the trial.

With more than an hour devoted to the courtroom proceedings -- many of them closely following the real arguments -- Inherit the Wind succeeds or fails on the basis of the drama of two men talking. I think it succeeds grandly, as these two old, titanic actors are given lines and scenes that allow for high drama centered around people talking, arguing, shouting, and occasionally mopping their brows in the steamy courtroom, in the steamy hotel, or on the steamy hotel porch. It's hot, dammit!

I imagine a lot of people would be turned off by a drama of ideas, especially one in which fundamentalist Christianity takes the intellectual and moral beating of a lifetime. I think it's swell, and in a way an obvious forerunner to the work of Aaron Sorkin, though here much of the talking is done while the characters remain mostly stationary. Highly recommended.

Thursday, September 13, 2012

Heartburst

Heartburst and Other Pleasures: written by Rick Veitch with Alan Moore; illustrated by Rick Veitch with Steve Bissette (collected 2008): This selection of Veitch's early 1980's graphic 'novel' Heartburst and a number of other short pieces from two decades is a pleasure to read.

Heartburst (really only 48 pages long and called a 'novel' when first published when, as Veitch notes in his introduction, the derived-from-the-French 'graphic album' would have made more sense) presents an Earth colony that has based its entire culture on the early American TV broadcasts that are just arriving on that world thanks to the pesky speed of light.

That Earth colony, a sort of quasi-Roman Catholic fascist tyranny, is also in the process of exterminating the intelligent natives of that planet for, among other things, being too sexually liberated.

Veitch does a nice job of playing in a very satiric, 1950's science-fictional universe, but with more sex and a little more nudity, and the quantum-spiritualism elements of the text are really quite charming. The whole thing would only be more enjoyable at two or three times the length, where certain elements (such as the travelling circus) might end up feeling more organic and a bit less forced.

The short pieces and sketches give brief snapshots of Veitch throughout his career. He's remained remarkably consistent, and as a bonus, the colours in this collection really 'pop': it looks terrific. Recommended.

Heartburst (really only 48 pages long and called a 'novel' when first published when, as Veitch notes in his introduction, the derived-from-the-French 'graphic album' would have made more sense) presents an Earth colony that has based its entire culture on the early American TV broadcasts that are just arriving on that world thanks to the pesky speed of light.

That Earth colony, a sort of quasi-Roman Catholic fascist tyranny, is also in the process of exterminating the intelligent natives of that planet for, among other things, being too sexually liberated.

Veitch does a nice job of playing in a very satiric, 1950's science-fictional universe, but with more sex and a little more nudity, and the quantum-spiritualism elements of the text are really quite charming. The whole thing would only be more enjoyable at two or three times the length, where certain elements (such as the travelling circus) might end up feeling more organic and a bit less forced.

The short pieces and sketches give brief snapshots of Veitch throughout his career. He's remained remarkably consistent, and as a bonus, the colours in this collection really 'pop': it looks terrific. Recommended.

Labels:

alan moore,

graphic novel,

heartburst,

rick veitch,

steve bissette

Execution and Remorse

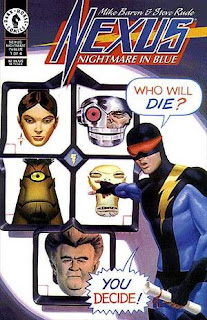

Nexus: Nightmare in Blue: written by Mike Baron; illustrated by Steve Rude and Gary Martin (1997): Nexus, that jolliest and jauntiest of comic book series about a brooding, 25th-century, human executioner of mass murderers, has now been around, in fits and starts, for about thirty years. Thirty years! And it now seems to be back at Dark Horse Comics again, after more than a decade in the self-published wilderness. This calls for hyperspeed!

Creators Mike Baron and Steve Rude have always done their best work together on Nexus. Here, in what I believe was the last Dark Horse miniseries prior to a lengthy hiatus and a brief flirtation with self-publishing, Nexus looks somewhat unusual in black and white, though he did start off his adventures in B&W with Capital Comics lo these many years gone. There's some brooding, some cosmic space-opera action, some developments in Nexus's relationship with long-term partner Sundra Peale, and a host of political shenanigans on the inhabitable moon called Ylum.

I wouldn't recommend this as a starting place -- for that, I'd say go to the actual starting place in either single issues or collected editions, if you can find them, and immerse yourself in the greatest superhero/space-opera mash-up comic book ever created.

Baron's writing is sharp here, in any case, and Steve Rude continues to showcase his oddly retro ability to combine cosmic action, heroic poses, and near-funny-animal cartooning into a potent blend. Nobody draws aliens like Rude. Or guys with a rocket instead of one foot. Recommended.

Creators Mike Baron and Steve Rude have always done their best work together on Nexus. Here, in what I believe was the last Dark Horse miniseries prior to a lengthy hiatus and a brief flirtation with self-publishing, Nexus looks somewhat unusual in black and white, though he did start off his adventures in B&W with Capital Comics lo these many years gone. There's some brooding, some cosmic space-opera action, some developments in Nexus's relationship with long-term partner Sundra Peale, and a host of political shenanigans on the inhabitable moon called Ylum.

I wouldn't recommend this as a starting place -- for that, I'd say go to the actual starting place in either single issues or collected editions, if you can find them, and immerse yourself in the greatest superhero/space-opera mash-up comic book ever created.

Baron's writing is sharp here, in any case, and Steve Rude continues to showcase his oddly retro ability to combine cosmic action, heroic poses, and near-funny-animal cartooning into a potent blend. Nobody draws aliens like Rude. Or guys with a rocket instead of one foot. Recommended.

Labels:

judah,

mike baron,

nexus,

space opera,

steve rude,

tyrone,

ylum

Tuesday, September 11, 2012

World's Worst

Wild Worlds: written by Alan Moore; illustrated by Travis Charest, Jim Baikie, Adam Hughes, and others (1997-99; collected 2007): From Alan Moore's pre-America's Best Comics, 'just paying the bills' phase comes this hodgepodge of Moore's non-WildC.A.T.S. work for the Wildstorm universe, which at the time was still a branch of Image Comics and not a branch of DC Comics.

OK, there is one WildC.A.T.S. story, an epilogue that doesn't work all that well with the other 13 or so issues it's an epilogue to. And those issues have their own collection, so why the epilogue appears here as well is...a mystery. I'm assuming it's probably because Travis Charest drew it, thus supplying the collection with one of its few artistic highpoints.

The best piece in the collection is a Majestic one-off depicting the immortal hero's adventures at the end of time, as entropy ends all. It's also reprinted elsewhere -- in a Majestic collection. But it is dandy, story and art.

The rest of the collection ranges from truly awful (the Spawn/WildC.A.T.S. miniseries features some of the worst 90's-style art I've ever seen professionally published. It could be used as a textbook-case on how NOT to draw superheroes. Or anything) to the competent (a Voodoo miniseries and a DV8 miniseries are both interesting, and Jim Baikie's art on the DV8 piece is typically enjoyable and slightly unusual for a superhero book). But really, not recommended unless you either get it deeply discounted (as I did) or are a rabid Alan Moore completist (as I am).

OK, there is one WildC.A.T.S. story, an epilogue that doesn't work all that well with the other 13 or so issues it's an epilogue to. And those issues have their own collection, so why the epilogue appears here as well is...a mystery. I'm assuming it's probably because Travis Charest drew it, thus supplying the collection with one of its few artistic highpoints.

The best piece in the collection is a Majestic one-off depicting the immortal hero's adventures at the end of time, as entropy ends all. It's also reprinted elsewhere -- in a Majestic collection. But it is dandy, story and art.

The rest of the collection ranges from truly awful (the Spawn/WildC.A.T.S. miniseries features some of the worst 90's-style art I've ever seen professionally published. It could be used as a textbook-case on how NOT to draw superheroes. Or anything) to the competent (a Voodoo miniseries and a DV8 miniseries are both interesting, and Jim Baikie's art on the DV8 piece is typically enjoyable and slightly unusual for a superhero book). But really, not recommended unless you either get it deeply discounted (as I did) or are a rabid Alan Moore completist (as I am).

Labels:

adam hughes,

alan moore,

dv8,

jim baikie,

majestic,

spawn,

travis charest,

voodoo,

wildc.a.t.s.,

wildstorm

Whole Lotta Rapine Going On

Triage by Richard Laymon, Edward Lee, and Jack Ketchum (2001): Originally printed as a limited-edition hardcover, Triage brought together three fairly famous horror writers to structure novellas around the same central premise: a guy walks into a place of work and starts shooting.

The late Richard Laymon's piece is the weakest of the three, an office-space thriller with a ridiculously hyper-competent, crazed killer and all the rape you could want, if you want such things. The ratio of 'rape' to 'vengeance for rape' is about 10-1, which gives the whole exercise about as unwholesome a feeling as I really need.

Edward Lee's piece is also preoccupied with sex, rape, and bad touching. It is pleasingly loopy at times, set as it is on a spaceship of the dominant, hyper-technologized fundamentalist Catholic Earth Empire. You won't see the twist ending coming, and it is a bit of a hoot, but all the vaginal probing that comes before that may blunt a lot of the impact.

Ketchum's concluding piece is both the best of the trio and the oddest, as the novella goes way off the reservation to give us the day-to-day life of a beaten-down writer who works at a bargain-basement literary agency. He's a sad sack...but a sad sack with two girlfriends, at least when the story starts, and an ex-wife who's turned into a lesbian.

Maybe the three writers misheard 'novella' as 'telenovella.' Sex and rape are mostly absent, and Ketchum's tale gives us a nice bit of characterization with the depressed protagonist. Still, there's nothing either horrifying or particularly thrilling about the story. As a whole or in parts, not recommended.

The late Richard Laymon's piece is the weakest of the three, an office-space thriller with a ridiculously hyper-competent, crazed killer and all the rape you could want, if you want such things. The ratio of 'rape' to 'vengeance for rape' is about 10-1, which gives the whole exercise about as unwholesome a feeling as I really need.

Edward Lee's piece is also preoccupied with sex, rape, and bad touching. It is pleasingly loopy at times, set as it is on a spaceship of the dominant, hyper-technologized fundamentalist Catholic Earth Empire. You won't see the twist ending coming, and it is a bit of a hoot, but all the vaginal probing that comes before that may blunt a lot of the impact.

Ketchum's concluding piece is both the best of the trio and the oddest, as the novella goes way off the reservation to give us the day-to-day life of a beaten-down writer who works at a bargain-basement literary agency. He's a sad sack...but a sad sack with two girlfriends, at least when the story starts, and an ex-wife who's turned into a lesbian.

Maybe the three writers misheard 'novella' as 'telenovella.' Sex and rape are mostly absent, and Ketchum's tale gives us a nice bit of characterization with the depressed protagonist. Still, there's nothing either horrifying or particularly thrilling about the story. As a whole or in parts, not recommended.

Labels:

edward lee,

jack ketchum,

richard laymon,

triage

Monday, September 3, 2012

Personal Best, Personal Beast

A Dangerous Method: adapted by Christopher Hampton from his play "The Talking Cure" and the book A Most Dangerous Method by John Kerr; directed by David Cronenberg; starring Keira Knightley (Sabina Spielrein), Viggo Mortensen (Sigmund Freud), Michael Fassbender (Carl Jung), Vincent Cassel (Otto Gross), and Sarah Gadon (Emma Jung) (2011): If you'd turned to someone 30 years or so ago after watching Scanners and told that person that David Cronenberg would soon become one of the world's greatest actors' directors, you'd have been laughed out of the theatre. But he did, and after eliciting career-best performances from Viggo Mortensen, Peter Weller, Jeremy Irons, and Ralph Fiennes, in A Dangerous Method he makes Keira Knightley look good, partially by making her look terrible.

As Carl Jung's patient-turned-mistress Sabina Spielrein, Knightley looks for most of the movie like she needs a sandwich. A lot of sandwiches. Her gauntness enhances her performance, though it is distracting at times -- how much of this is method and how much of this is madness? Still, it's like nothing she's ever done: for the first time on-screen, Knightley isn't lovely but dramatically inert.

Fassbender and Mortensen have the much less showy roles as the more outwardly controlled Jung and Freud, respectively. But they do a lot with those roles -- Mortensen exudes disappointment at times, while Fassbender, one of the more controlled actors out there, uses that control and reserve to good advantage as the outwardly respectable Jung, who is inwardly and sexually on the brink of his great voyage into the collective consciousness and unconsciousness of the human race.

The movie charts the deteroriation of Freud and Jung's relationship at the dawn of psychoanalysis, as they go from master and apprentice to rivals dismissive of each other's theories of the human mind. But Sabina, who eventually becomes a psychoanalyst herself, has her own theories which seek to combine the approaches of the two -- and as she reminds Jung at the end, he used Freud's theories and practices to cure her of her psychiatric ailments.

Cronenberg's direction remains mostly transparent and unshowy throughout -- he's always been more for mise-en-scene anyway, and the composition of many shots ranges from lovely to subtly disturbing. I don't know that this is a great movie, but it's a very good movie on a difficult-to-film subject. Recommended.

As Carl Jung's patient-turned-mistress Sabina Spielrein, Knightley looks for most of the movie like she needs a sandwich. A lot of sandwiches. Her gauntness enhances her performance, though it is distracting at times -- how much of this is method and how much of this is madness? Still, it's like nothing she's ever done: for the first time on-screen, Knightley isn't lovely but dramatically inert.

Fassbender and Mortensen have the much less showy roles as the more outwardly controlled Jung and Freud, respectively. But they do a lot with those roles -- Mortensen exudes disappointment at times, while Fassbender, one of the more controlled actors out there, uses that control and reserve to good advantage as the outwardly respectable Jung, who is inwardly and sexually on the brink of his great voyage into the collective consciousness and unconsciousness of the human race.

The movie charts the deteroriation of Freud and Jung's relationship at the dawn of psychoanalysis, as they go from master and apprentice to rivals dismissive of each other's theories of the human mind. But Sabina, who eventually becomes a psychoanalyst herself, has her own theories which seek to combine the approaches of the two -- and as she reminds Jung at the end, he used Freud's theories and practices to cure her of her psychiatric ailments.

Cronenberg's direction remains mostly transparent and unshowy throughout -- he's always been more for mise-en-scene anyway, and the composition of many shots ranges from lovely to subtly disturbing. I don't know that this is a great movie, but it's a very good movie on a difficult-to-film subject. Recommended.

Sunday, September 2, 2012

Swamped

Swamp Thing: Raise Them Bones: written by Scott Snyder; illustrated by Yanick Paquette and Marco Rudy (2011-2012; collected 2012): I'm not sure there was any character who more needed a clean reboot than Swamp Thing when DC implemented its line-wide 'soft' reboot late last summer. Alas, this was indeed a soft reboot -- apparently, pretty much everything that happened to Swamp Thing in 40 years of comic-book adventures happened to him anyway. It all just happened in five years. Or something. We still haven't really been told.

With this loopy, continuity-albatross around their necks, Snyder, Paquette and Rudy do a solid job of giving us a partially rebooted Swamp Thing who has yet to be Swamp Thing even though he already was Swamp Thing. I'm not explaining that last bit any further. Paquette and Rudy draw some lovely, gooshy creature work, and a suitably gloopy, grungy, fertile swamp environment; Snyder deftly sketches out characters who are both familiar and subtly changed.

Unfortunately, Swamp Thing, like a number of other New 52 titles, drops us into a lengthy storyline that, as of this writing, shows no signs of wrapping up any time soon. We're essentially reading the longest origin story for Swamp Thing ever written, by a factor of five or six and climbing.

And we're also in a storyline that intimately crosses over into an equally lengthy storyline in Animal Man. By the time it's all over, the opening storyline of the new Swamp Thing will also be the single longest Swamp Thing arc in comic-book history. I've enjoyed it so far, but I enjoy it less and less as I go along. None of the issues stand alone, and some of the issues require a parallel reading of Animal Man as well.

Frankly, Captain, I'm exhausted.

I'll keep reading, but I sincerely hope that after this enormous opening, we get a few stand-alone issues and short arcs. If we don't, here and elsewhere in the New 52 line, DC will founder on its new continuity with astonishing rapidity. Recommended.

With this loopy, continuity-albatross around their necks, Snyder, Paquette and Rudy do a solid job of giving us a partially rebooted Swamp Thing who has yet to be Swamp Thing even though he already was Swamp Thing. I'm not explaining that last bit any further. Paquette and Rudy draw some lovely, gooshy creature work, and a suitably gloopy, grungy, fertile swamp environment; Snyder deftly sketches out characters who are both familiar and subtly changed.

Unfortunately, Swamp Thing, like a number of other New 52 titles, drops us into a lengthy storyline that, as of this writing, shows no signs of wrapping up any time soon. We're essentially reading the longest origin story for Swamp Thing ever written, by a factor of five or six and climbing.

And we're also in a storyline that intimately crosses over into an equally lengthy storyline in Animal Man. By the time it's all over, the opening storyline of the new Swamp Thing will also be the single longest Swamp Thing arc in comic-book history. I've enjoyed it so far, but I enjoy it less and less as I go along. None of the issues stand alone, and some of the issues require a parallel reading of Animal Man as well.

Frankly, Captain, I'm exhausted.

I'll keep reading, but I sincerely hope that after this enormous opening, we get a few stand-alone issues and short arcs. If we don't, here and elsewhere in the New 52 line, DC will founder on its new continuity with astonishing rapidity. Recommended.

Labels:

animal man,

arcane,

marco rudy,

new 52,

scott snyder,

swamp thing,

yanick paquette

Nail Fail

JLA: The Nail: written and pencilled by Alan Davis; inked by Mark Farmer (1998; collected 1999): In this Elseworlds miniseries (or 'What If?' were it from Marvel), the DC Universe suffers from the apparent non-existence of Superman because of a nail in Ma and Pa Kent's truck tire on the day of baby Kal-El's arrival from Krypton.

Alan Davis has always been a very clean, exciting superhero artist, firmly in the tradition of Neal Adams and John Byrne in the world of the hyper-real. He's also turned out to be a solid writer. The Nail feels like a throwback to the early 1980's or even earlier. It may be aimed at some sort of adult, but it nonetheless zips along in a breezy and entertaining fashion, without too much psychobabble despite some of the heavy-duty shenanigans that go on.

Without Superman, the present-day Justice League of America finds itself in a world where many normal citizens hate and fear super-heroes. Without Superman, DC-Earth has become Marvel-Earth. Or maybe just a foreshadowing of the New 52. In any case, someone or something is causing super-heroes and super-villains alike to vanish while simultaneously fanning the flames of xenophobia. This looks like a job for...oh, right.

A new edition collecting both The Nail and its excellent sequel, Another Nail, would be nice -- they really form one narrative. The biggest laugh here comes from the identity of the supervillain behind the woes of the JLA. It's at once weirdly funny and, given the thematic relevance of the whole 'Nail' concept -- of greater and greater consequences resulting from one small changed moment -- completely apt. Recommended.

Alan Davis has always been a very clean, exciting superhero artist, firmly in the tradition of Neal Adams and John Byrne in the world of the hyper-real. He's also turned out to be a solid writer. The Nail feels like a throwback to the early 1980's or even earlier. It may be aimed at some sort of adult, but it nonetheless zips along in a breezy and entertaining fashion, without too much psychobabble despite some of the heavy-duty shenanigans that go on.

Without Superman, the present-day Justice League of America finds itself in a world where many normal citizens hate and fear super-heroes. Without Superman, DC-Earth has become Marvel-Earth. Or maybe just a foreshadowing of the New 52. In any case, someone or something is causing super-heroes and super-villains alike to vanish while simultaneously fanning the flames of xenophobia. This looks like a job for...oh, right.

A new edition collecting both The Nail and its excellent sequel, Another Nail, would be nice -- they really form one narrative. The biggest laugh here comes from the identity of the supervillain behind the woes of the JLA. It's at once weirdly funny and, given the thematic relevance of the whole 'Nail' concept -- of greater and greater consequences resulting from one small changed moment -- completely apt. Recommended.

Labels:

alan davis,

another nail,

DC Comics,

elseworlds,

jla,

justice league of america,

superman,

the nail

Yuma Guma

3:10 to Yuma: adapted by Halsted Welles from a short story by Elmore Leonard; directed by Delmer Daves; starring Glenn Ford (Ben Wade), Van Heflin (Dan Evans), Felicia Farr (Emmy) and Leora Dana (Alice Evans) (1957): Terse, tight, beautifully photographed Western in which an ordinary farmer (Van Heflin) gets drafted to get a ruthless but charming robber (Glenn Ford, cast against type to good effect) to the train on time. It's essentially Planes, Trains, and Automobiles with horses and guns.

Van Heflin, with his lumpy potato bag of a face, always looked like the forerunner of Gene Hackman, an Everyman thrust onto Hollywood's A-list through some improbable chain of events. He's excellent here as the conflicted Wade, who ultimately sees the job through because he's disgusted by the murders that occurred during the robberies -- though he also wants to appear to be a hero to his wife and sons.

Ford plays robber Ben Wade as a sinister but occasionally sentimental presence. He has justifications for everything he does, but he also has a rudimentary code of honour when it comes to dealing with people, even the people he's robbing or the people who are holding him prisoner. The battle of wits between him and Van Heflin is tense and enjoyable, and the ending both logical and somewhat surprising. Recommended.

Van Heflin, with his lumpy potato bag of a face, always looked like the forerunner of Gene Hackman, an Everyman thrust onto Hollywood's A-list through some improbable chain of events. He's excellent here as the conflicted Wade, who ultimately sees the job through because he's disgusted by the murders that occurred during the robberies -- though he also wants to appear to be a hero to his wife and sons.

Ford plays robber Ben Wade as a sinister but occasionally sentimental presence. He has justifications for everything he does, but he also has a rudimentary code of honour when it comes to dealing with people, even the people he's robbing or the people who are holding him prisoner. The battle of wits between him and Van Heflin is tense and enjoyable, and the ending both logical and somewhat surprising. Recommended.

Labels:

3:10 to Yuma,

glenn ford,

high noon,

van heflin,

westerns

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)