Sunday, February 7, 2016

Three Chose Adventure!

The Straight Story: written by John Roach and Mary Sweeney; directed by David Lynch; starring Richard Farnsworth (Alvin Straight), Sissy Spacek (Rose), Everett McGill (Tom the John Deere Dealer), Kevin and John Farley (The Twins), and Harry Dean Stanton (Lyle Straight) (1999): David Lynch had no part in the writing of this movie so far as I can tell, a first in his career. The visuals, the soundscape, and the performances of the actors are all Lynchian, though.

It's a brilliant, based-on-a-true-story look at one stubborn old man on what seems to be a quixotic quest to visit his ailing brother whom he's not talked to in a decade. The quixotic part concerns the fact that our protagonist Alvin Straight is too near-blind to drive a car and too poor to afford a bus or train visit from his home in Iowa to his brother's home in Wisconsin. So he decides to make a six-week trek on a John Deere riding lawnmower pulling a hand-modified, covered cart.

And he does. The bulk of the movie concerns that trek going down the road, the people Straight meets along the way, and the natural landscapes through which he passes, quietly observing. Lynch punctuates the movie with Sublime scenes of thunderstorms, vast fields, and the starry sky above, all of them subject to Straight's quiet regard.

It's the acting, though, that makes The Straight Story especially special. This was a cancer-wracked Richard Farnsworth's final role before his death. His Alvin Straight is stoic and stubborn, but also extremely protective of those whom he loves -- including his mentally challenged adult daughter, marvelously realized by Sissy Spacek. He's a straight shooter. And his stubborn decency wins over everyone whom he encounters. It's an extraordinarily sweet movie, especially for Lynch, but I don't think it's as out-of-character as many critics did at the time.

For one, Lynch has always been fascinated by idiosyncratic characters. Well, he must be -- he's written so many of them! Alvin Straight is perhaps most similar to the eponymous character in The Elephant Man, achingly human while faced with hardship. But the idiosyncratic characters support the movie throughout as well, from the fine Everett McGill's (Big Ed!) John Deere dealer to the fellow World War Two vet with whom Straight commiserates about the mental scars of those long-ago battles.

And while the movie takes its stubborn optimism from Alvin Straight, it's also shot through with darkness remembered and long contemplated by Straight, from a horrible secret of his World War Two career as a sniper to the bitterness and alcoholism that led to falling out with his brother. Maybe the movie contains one too many Alvin-delivered homilies about the importance of family, but I think what's put on the screen earns those homilies their imaginative space. It may be a sweetheart of a movie, but it's the dark moments that put that sweetness into high relief. Highly recommended.

Garth Ennis' The Demon Volume 1: written by Garth Ennis; illustrated by John McCrea and others (1993-94/Collected 2015): Ennis and McCrea's anarchic, vulgar take on Jack Kirby's non-anarchic, non-vulgar Etrigan the Demon is a hoot for those with a strong stomach. It's no more faithful to Kirby's original conception of a demon who fights on the side of the angels than, well, pretty much every other take on The Demon after Kirby's. Indeed, the only comic book that ever came close to Kirby's energetic mix of super-heroism and the supernatural is Mike Mignola's Hellboy.

Ennis and McCrea, like Alan Moore and Matt Wagner before them, make Etrigan a barely controlled monster. They make the human Etrigan shares a body with, Jason Blood, into a whiny incompetent. They make the various supporting characters into buffoons and punchlines. So it goes. It all works because Ennis and McCrea are really good at ultraviolent horror comedy. It also works because they introduce their super-powered hitman character (cleverly dubbed Hitman) in the course of these issues. Hitman would get his own series. As is pretty much always the case with Ennis, he'd seem a lot more comfortable and a lot less scabrous writing his own character.

The standout story arc here sees Ennis and McCrea bring back DC's venerable weird war series The Haunted Tank. The cognitive dissonance generated by a story of an American tank haunted by a Confederate general taking on a bunch of resurrected, supernatural Nazis with the help of a nihilistic Demon is a wee bit mind-blowing. Perhaps never moreso than in a scene in which the Demon explains to the Nazis why he finds them repugnant. It's crazy fun, and it allows Ennis to himself resurrect some of the ridiculous maneuvers the dinky little Haunted Tank once performed so as to defeat seemingly endless hordes of vastly superior Nazi machinery.

Is this Kirbyesque? No. And Ennis' decision to have Etrigan speak in rhymes all the time -- based on a long-standing, DC-wide misreading of Kirby's original Etrigan , who only occasionally spoke in rhyme -- can make for some truly godawful writing at points. But, you know, Nazi zombies in tanks! Recommended.

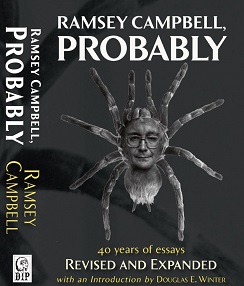

Ramsey Campbell, Probably (1968-2015/Collected in 2015 Revised Edition) by Ramsey Campbell, edited by S.T. Joshi: 40 years of non-fiction pieces by World's Greatest Horror Writer Ramsey Campbell. There are autobiographical pieces which illuminate Campbell's often harrowing early life, essays on various writers, pieces on social issues related to horror, and essays and introductions originally written for Campbell's novels and short-story collections.

In all, they're dandy. And so many of them in this big book from PS Publishing! Campbell is thoughtful and often self-effacing when he writes about his own work, and those essays that do this offer a wealth of information about how and why certain decisions were made in the writing process, and what Campbell thinks about those decisions in retrospect.

He's also debilitatingly funny in many of the essays, never moreso than when he deals with The Highgate Vampire hoax. There's also hilarity to be had in portions of his self-appraisal (for some reason, a section on his attempt to include the word 'shit' in a Lovecraftian story submitted to August Derleth's Arkham House nearly had me lying on the floor).

His essays on writers are occasionally scathing but for the most part positive. A melancholy essay on the late John Brunner stands out as a painful meditation on what happens when a very good writer is forgotten in today's publishing climate. A wide-ranging essay on the novels of James Herbert is a sensitive reappraisal of that (alas, also late) best-selling writer's work as a foundational stratum of working-class, English horror shot through with deeply held social concerns not usually seen in English horror up to that time. Many of the writers Campbell writes about are also friends, thus shedding a certain personal light on writers ranging from Robert Aickman to the (then) Poppy Z. Brite.

General pieces include the almost-obligatory '10 horror movies for a desert island' essay, several examinations of horror in general and the general public's attitude towards horror, the 'Video Nasties' censorship hysteria in the Great Britain of the 1980's and early 1990's, and examinations of the history of horror. Campbell's lengthy autobiographical essay "How I Got Here" is also invaluable in understanding his life and work. He's almost painfully self-revelatory at points, while remaining refreshingly free of self-pity.

Oh, and there's an essay on British spanking-based pornography. Really, you can't go wrong with this collection. How often is one going to find revelatory close readings of major H.P. Lovecraft stories and brief 'plot' synopses of faux-English-school-girl spanking pornography in the same book? Highly recommended.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.