Louis Riel: written and illustrated by Chester Brown (2003): One of Canada's tragic true tales of nation-building comes to life in Chester Brown's much-acclaimed graphic novel. Brown's art-style is sharp-lined and cartoony here. In the introduction, he notes the judgement of others that there's a lot of Herge's Tintin at work here while explaining that Little Orphan Annie's Harold Gray was the specific inspiration for the work done here. It's still of a piece artistically with Brown's other work while nonetheless being distinctive, and distinctively different from its influences even as one can see them manifest in Brown's style.

This is perhaps the cleanest, loveliest art of Brown's distinguished career. He modestly asserts that he's no competition for either Herge or Gray in the introduction. Well, he is Canadian, and darn, this is fine black-and-white cartooning.

Copious endnotes explain Brown's sources and where Brown changed history in minor ways for the purposes of drama. He didn't have to change much. The saga of reluctant revolutionary Louis Riel, the Metis of what would become Manitoba, Prime Minister John A. Macdonald, the greedy and manipulative Hudson's Bay Company, and the building of the Canadian Pacific Railroad supply pretty much all the drama and absurdity, the comedy and the pathos, that one could want out of a historical event.

One of the most fascinating decisions Brown seems to have made in creating this book was to essentially make it an 'All-Ages' project, with little swearing and no nudity or sex. No nudity or sex in a Chester Brown comic? Holy Moley!

I rarely find books to be 'unputdownable,' but this one kept me reading early into the morning before I finally succombed to sleep. It's a brilliant accomplishment. Regardless of where one comes down on the issue of Riel -- martyr? saint? murderer? madman? -- this book seems almost necessary to any Canadian's bookshelf. It's heart-breaking, and heart-breakingly good. Highly recommended.

Thursday, July 31, 2014

Wednesday, July 30, 2014

H.P. Lovecraft's Holiday Grab-Bag

The Evil People: edited by Peter Haining (1968) containing the following stories:

The Evil People: edited by Peter Haining (1968) containing the following stories:The Nocturnal Meeting by William Harrison Ainsworth; The Peabody Heritage by H. P. Lovecraft and August Derleth; The Witch's Vengeance by William B. Seabrook; The Snake by Dennis Wheatley; Prince Borgia's Mass by August Derleth; Secret Worship by Algernon Blackwood; The Devil-Worshipper by Francis C. Prevot; Archives of the Dead by Basil Copper; Mother of Serpents by Robert Bloch; Cerimarie by Arthur J. Burks; The Witch by Shirley Jackson; Homecoming by Ray Bradbury; Never Bet the Devil Your Head by Edgar Allan Poe.

Certainly not one of the prolific anthologist Peter Haining's better efforts in the horror field, but nonetheless interesting and informative from a historical perspective. Many of the stories were little- or uncollected prior to their appearance here. The Evil People offers a survey of witchcraft and voodoo in Anglo-American literature over about a century.

Overt racism figures in several stories. There aren't a lot of scares here, though it's fascinating to see how witchcraft was depicted in some 19th-century stories and excerpts. Poe's story is one of his comic trifles; the Derleth-Lovecraft 'collaboration' is one of those stories written by Derleth from a few notes scrawled by Lovecraft; Basil Copper's story is strong right up to a fizzle of a climax. The Shirley Jackson, Ray Bradbury, and Algernon Blackwood stories are all excellent. Recommended for historical purposes.

Eldritch Tales: A Miscellany of the Macabre by H.P. Lovecraft and others; edited by Stephen Jones (2011), containing the following pieces by H.P. Lovecraft and others where indicated:

A Reminiscence of Dr. Samuel Johnson (1917); Afterword: Lovecraft in Britain by Stephen Jones; Azathoth (1921); Beyond the Wall of Sleep (1919); Celephaïs (1922); Despair (1919); Ex Oblivione (1921); Facts Concerning the Late Arthur Jermyn and His Family(1920); The Festival (1925); Fungi from Yuggoth (1931); Hallowe'en in a Suburb (1926); He (1926); History of the Necronomicon (1938); Hypnos (1922); Ibid (1938); In a Sequester'd Providence Churchyard Where Once Poe Walk'd (1937); Memory (1923); Nathicana (1927); Nyarlathotep (2008); Poetry and the Gods (1920) by H. P. Lovecraft and Anna Helen Crofts; Polaris (1920) by H. P. Lovecraft; Psychopompos: A Tale in Rhyme (1919); Supernatural Horror in Literature (1927); The Alchemist (1916); The Ancient Track; The Beast in the Cave (1918); The Book (1938); The Challenge from Beyond (1935); The Crawling Chaos (1921) by Winifred V. Jackson and H. P. Lovecraft; The Descendant (1926); The Electric Executioner (1930) by H. P. Lovecraft and Adolphe de Castro; The Evil Clergyman (1939); The Festival (1925) by H. P. Lovecraft; The Green Meadow (1918) by Winifred V. Jackson and H. P. Lovecraft; The Horror at Martin's Beach (1923) by H. P. Lovecraft and Sonia Greene; The House(1920); The Last Test (1928) by H. P. Lovecraft and Adolphe de Castro; The Messenger (1938); The Moon-Bog (1926); The Nightmare Lake (1919); The Other Gods (1933); The Picture in the House (1919); The Poe-et's Nightmare (1918); The Quest of Iranon (1935); The Street (1920); The Temple (1925); The Terrible Old Man (1921); The Thing in the Moonlight (1934); The Tomb (1922); The Transition of Juan Romero (1919); The Trap (1932) by H. P. Lovecraft and Henry S. Whitehead; The Tree (1921); The Very Old Folk (1927); The White Ship (1925); The Wood (1929); Two Black Bottles (1927) by H. P. Lovecraft and Wilfred Blanch Talman; and What the Moon Brings (1922).

The second of Gollancz's new line of H.P. Lovecraft collections for the British market covers a lot of ground among Lovecraft's lesser-read works. There's juvenalia, Dream-Cycle stories, collaborations, revisions, poems, and Lovecraft's excellent critical-survey essay, "Supernatural Horror in LIterature."

If the reader has already read Lovecraft's better-known works from his later years as a writer, this book offers a far-ranging sample of his development as a writer. Some of the juvenalia is terrible, but all of it is at the very least interesting. And much of the poetry -- especially the cosmic/comic "The Poe-et's Nightmare" (1918) and the horror-poem cycle of sonnets, Fungi from Yuggoth (1930-31) -- is surprisingly good. Highly recommended to people who want more H.P. Lovecraft; lightly recommended to people who don't know who H.P. Lovecraft is.

Tuesday, July 29, 2014

Strange Bedfellows

Quick Change: adapted by Howard Franklin from the novel by Jay Cronley; directed by Bill Murray and Howard Franklin; starring Bill Murray (Grimm), Geena Davis (Phyllis), Randy Quaid (Loomis), and Jason Robards (Rotzinger) (1990): This is almost a 'lost' Bill Murray movie, one that didn't do well at the summer box office back in 1990. I think it may be too low key to have ever been a huge success, but it also got lost in a flood of blockbusters that year. As is, it's the only movie which Murray also produced and (co-)directed, and it's really good.

Quick Change follows a bank heist masterminded by Murray's character. That part goes smoothly. However, getting out of New York turns out to be the real problem. Terrific supporting work from Geena Davis, Randy Quaid, Tony Shaloub, and Jason Robards makes a zippy script flow smoothly even if the plan does not. Murray's character, while sarcastic as always, nonetheless also resonates with what appear to be warmer human feelings. It's a fine, neglected performance from Murray in a fine, neglected film. Recommended.

And Then There Were None: adapted by Dudley Nichols from the play Ten Little Indians by Agatha Christie; directed by Rene Clair; starring Barry Fitzgerald (Quincannon), Walter Huston (Armstrong), June Duprez (Vera Claythorne) and Louis Hayward (Philip Lombard) (1945): Adapted from Agatha Christie's play, itself an adaptation of her own novel which at one point had a truly regrettable title in Great Britain (look it up). Fun though somewhat stagy and a bit overlong, the movie adapts a book that really works as the foundational work for an astonishing number of horror movies and thrillers in which a rising body count lifts all tides. Walter Huston and Barry Fitzgerald pretty much act everyone other than Judith Anderson right off the screen. Recommended.

The Grudge: adapted by Stephen Susco from the screenplay by Takashi Shimizu for Ju-On; directed by Takashi Shimizu; starring Sarah Michelle Gellar (Karen), Jason Behr (Doug), William Mapother (Matthew), Bill Pullman (Peter), Grace Zabriskie (Emma), Clea DuVall (Jennifer), Ted Raimi (Alex), and Ryo Ishibashi (Nakagawa) (2004): The sprung rhythms of this horror movie, adapted from a Japanese horror movie directed by the same director, sometimes yield good scares. By the end, though, the ridiculous omnipotence of the ghosts makes the movie an exercise in the cliched nihilism of most American horror movies.

No one even tries to find a religious or spiritual solution to the ghost problem, though there is a scene early in the film which suggests either an abandoned plot thread or a red herring. The logic of the ghosts in the movie would seem to suggest that everyone on the planet should have been murdered by spirits long ago. They can do anything and go anywhere. And what is up with the hair? Lightly recommended because it's really short.

Night of the Living Dead: written by George Romero and John Russo; directed by Tom Savini; starring Tony Todd (Ben) and Patricia Tallman (Barbara) (1990): 1990 remake of George Romero's genre-defining zombie masterpiece of 1968. Romero supplies a new script, while make-up wizard Tom Savini directs for the first time. The whole experience loses something in colour, but the thing does build to a satisfying climax.

Stuntwoman Patricia Tallman makes for a good heroine, much less passive than the original Barbara, while Tony Todd is sharp and sympathetic as her brother-in-arms (though not the actual brother who says that famous line I'm not going to repeat). The social satire is much more pointed this time around, and much more in the vein of Romero's Dawn of the Dead. His zombies may be dangerous, but they're also sources of sorrow and pity in a way few other film-makers have even even tried to capture. And unlike so many younger American horror film directors, Romero isn't afraid to mix a bit of hope in with the despair and the disgust. Recommended.

Quick Change follows a bank heist masterminded by Murray's character. That part goes smoothly. However, getting out of New York turns out to be the real problem. Terrific supporting work from Geena Davis, Randy Quaid, Tony Shaloub, and Jason Robards makes a zippy script flow smoothly even if the plan does not. Murray's character, while sarcastic as always, nonetheless also resonates with what appear to be warmer human feelings. It's a fine, neglected performance from Murray in a fine, neglected film. Recommended.

And Then There Were None: adapted by Dudley Nichols from the play Ten Little Indians by Agatha Christie; directed by Rene Clair; starring Barry Fitzgerald (Quincannon), Walter Huston (Armstrong), June Duprez (Vera Claythorne) and Louis Hayward (Philip Lombard) (1945): Adapted from Agatha Christie's play, itself an adaptation of her own novel which at one point had a truly regrettable title in Great Britain (look it up). Fun though somewhat stagy and a bit overlong, the movie adapts a book that really works as the foundational work for an astonishing number of horror movies and thrillers in which a rising body count lifts all tides. Walter Huston and Barry Fitzgerald pretty much act everyone other than Judith Anderson right off the screen. Recommended.

The Grudge: adapted by Stephen Susco from the screenplay by Takashi Shimizu for Ju-On; directed by Takashi Shimizu; starring Sarah Michelle Gellar (Karen), Jason Behr (Doug), William Mapother (Matthew), Bill Pullman (Peter), Grace Zabriskie (Emma), Clea DuVall (Jennifer), Ted Raimi (Alex), and Ryo Ishibashi (Nakagawa) (2004): The sprung rhythms of this horror movie, adapted from a Japanese horror movie directed by the same director, sometimes yield good scares. By the end, though, the ridiculous omnipotence of the ghosts makes the movie an exercise in the cliched nihilism of most American horror movies.

No one even tries to find a religious or spiritual solution to the ghost problem, though there is a scene early in the film which suggests either an abandoned plot thread or a red herring. The logic of the ghosts in the movie would seem to suggest that everyone on the planet should have been murdered by spirits long ago. They can do anything and go anywhere. And what is up with the hair? Lightly recommended because it's really short.

Night of the Living Dead: written by George Romero and John Russo; directed by Tom Savini; starring Tony Todd (Ben) and Patricia Tallman (Barbara) (1990): 1990 remake of George Romero's genre-defining zombie masterpiece of 1968. Romero supplies a new script, while make-up wizard Tom Savini directs for the first time. The whole experience loses something in colour, but the thing does build to a satisfying climax.

Stuntwoman Patricia Tallman makes for a good heroine, much less passive than the original Barbara, while Tony Todd is sharp and sympathetic as her brother-in-arms (though not the actual brother who says that famous line I'm not going to repeat). The social satire is much more pointed this time around, and much more in the vein of Romero's Dawn of the Dead. His zombies may be dangerous, but they're also sources of sorrow and pity in a way few other film-makers have even even tried to capture. And unlike so many younger American horror film directors, Romero isn't afraid to mix a bit of hope in with the despair and the disgust. Recommended.

Sunday, July 27, 2014

Big Bunny Boom

we3: written by Grant Morrison; illustrated by Frank Quitely and Jamie Grant (2004, collected 2005): Bandit the dog, Tinker the cat, Pirate the rabbit: 1, 2, and 3 of we3. They were pets. They were stolen. A secret American military project turned them into super-soldiers -- heavily armed, heavily armoured, trained to work as a team, and with a boost in intelligence from the machines grafted to them.

But after a final test run, they're to be 'put down.' The next phase of the program will involve larger animals specially bred and trained to replace soldiers on the battlefield. Weapon 4 already waits in its pen, too dreadful to be deployed anywhere near non-hostile civilians. there are kinks to work out.

Grant Morrison and Frank Quitely riff in unusual ways on things like the Jason Bourne books, 'lost-animal' novels that include The Incredible Journey, Japanese manga, and funny-animal comics with their talking animals. We cut between the humans and the animals for much of the narrative. The animals have developed a rudimentary language derived from English. They've also maintained their survival instincts: once they hear they're about to be killed, they escape in search of a nebulous and mostly forgotten 'Home.' They don't remember their names, but one sympathetic scientist does.

Funny, affecting, and not completely improbable, we3 also pointedly comments on both our mistreatment of animals and our dehumanization of soldiers in a quest for the perfect killing machine. The animals, already gifted by nature with reflexes and senses superior to human beings, make human super-soldiers like Captain America or Jason Bourne look like amateurs. With a dog as a tank, a cat as a fast-striking assassin, and a rabbit as a mine- and poison-gas-laying version of the Cadbury Easter Rabbit, we3 stages a battle that escalates until the powers that be deploy the terrible fourth weapon.

It's a thrilling ride, beautifully illustrated by Quitely and movingly written by Morrison. Moments of humour erupt throughout the carnage, as do moments of sadness. The dog still wants to be a good dog in relation to people. The cat just wants to get the Hell out of there. And the rabbit, the rabbit keeps saying, 'Uh oh' and blowing stuff up. Highly recommended.

But after a final test run, they're to be 'put down.' The next phase of the program will involve larger animals specially bred and trained to replace soldiers on the battlefield. Weapon 4 already waits in its pen, too dreadful to be deployed anywhere near non-hostile civilians. there are kinks to work out.

Grant Morrison and Frank Quitely riff in unusual ways on things like the Jason Bourne books, 'lost-animal' novels that include The Incredible Journey, Japanese manga, and funny-animal comics with their talking animals. We cut between the humans and the animals for much of the narrative. The animals have developed a rudimentary language derived from English. They've also maintained their survival instincts: once they hear they're about to be killed, they escape in search of a nebulous and mostly forgotten 'Home.' They don't remember their names, but one sympathetic scientist does.

Funny, affecting, and not completely improbable, we3 also pointedly comments on both our mistreatment of animals and our dehumanization of soldiers in a quest for the perfect killing machine. The animals, already gifted by nature with reflexes and senses superior to human beings, make human super-soldiers like Captain America or Jason Bourne look like amateurs. With a dog as a tank, a cat as a fast-striking assassin, and a rabbit as a mine- and poison-gas-laying version of the Cadbury Easter Rabbit, we3 stages a battle that escalates until the powers that be deploy the terrible fourth weapon.

It's a thrilling ride, beautifully illustrated by Quitely and movingly written by Morrison. Moments of humour erupt throughout the carnage, as do moments of sadness. The dog still wants to be a good dog in relation to people. The cat just wants to get the Hell out of there. And the rabbit, the rabbit keeps saying, 'Uh oh' and blowing stuff up. Highly recommended.

Labels:

captain america,

frank quitely,

grant morrison,

jason bourne,

super-soldier,

we3

Never the End!

The Jack Kirby Omnibus Volume 1 (Featuring Green Arrow): written and drawn by Jack Kirby and others (1947-1958; this edition 2011): Collecting most of writer-artist Jack Kirby's miscellaneous work for DC in the 1940's and 1950's, this collection also features a ten-story run on Green Arrow that might have really jazzed the character up had DC editors not named Julius Schwartz not been constitutionally opposed to jazzing anything up in the 1950's.

The one-and-done stories for DC's mystery and horror comics (and one Western) are enjoyable. Many play with material that would resurface later in Kirby's career, most notably a guest appearance by the Norse god Thor and some Easter-Island aliens who look a lot like the creatures from Saturn in Thor's first appearance at Marvel. Kirby didn't write the dialogue for most of the stories, at least not officially -- DC was also opposed to artists writing their own stories. Weird old 50's DC!

DC was extremely controlling and buttoned-down during the time of Kirby's work collected here. That means a certain amount of reining-in for Kirby, especially in terms of panel composition. Still, there's tons of fascinating stuff here. And the Green Arrow material suggests a science-fictional path for the character that might have lifted him out of years upon years of irrelevance. Cool beans. Recommended.

The Jack Kirby Omnibus Volume 2 (Featuring Super Powers): written and drawn by Jack Kirby and others (1951-1986; collected 2012): This Kirby omnibus collects all of the Jack Kirby stories and story arcs too short to get their own volumes. It spans quite a range. The Black Magic material herein actually comes from the pre-Comics Code 1950's; DC republished the stories they'd acquired from another publisher in the 1970's. And the volume ends with Kirby's last full-length comic book, the final issue of the second Super Powers miniseries, from 1986.

In between are bizarre concepts galore. The 1970's Sandman series would lead pretty much directly to Neil Gaiman's award-winning series of the 1980's. There are one-shots that attempt to cash in on the kung-fu craze (Richard Dragon), the sword-and-sorcery craze (Atlas), revivals of 1940's heroes (Manhunter), revivals of 1940's concepts (the kid-gang comic in The Dingbats of Danger Street), an attempt to focus a DC book on a supervillain rather than a hero (Kobra), and the rare air of a story featuring art from both Kirby and the great Alex Toth.

The lengthy volume (over 600 pages) also features Kirby's last stories of the New Gods, the characters he created when he came to DC in the early 1970's. Darkseid and company appear in the two Super Powers miniseries. In order to get Kirby royalty money for characters created before royalty provisions were attached, some combination of DC executives Paul Levitz, Dick Giordano, and Jenette Kahn had Kirby do minor redesigns on the New Gods characters as part of their inclusion in the new installment in the Super Friends franchise, Super Powers.

Kirby plotted the first miniseries and drew the final issue, with Joey Cavalieri scripting and Adrian Gonzales drawing the first four issues. The second miniseries was written by Paul Kupperberg and pencilled by Kirby. As the Super Powers team was essentially the Justice League, we get Kirby's late-career versions of Superman, Wonder Woman, Dr. Fate, and a host of others. Kirby's failing vision sometimes caused some odd bits of perspective in the 1980's, but overall it's a delight to see him pencilling both his own creations and DC's greatest heroes. His Wonder Woman is convincingly imposing, among other things, and we even get a return to Easter Island, with its alien statues waiting to be reborn.

Greg Theakston does a great job inking this last of Kirby's full-length works, and Kupperberg's scripting is suitably clever and bombastic. Technically (and bizarrely, I guess), this is the last work in Kirby's New Gods saga by Kirby himself. While it's not 'really' Kirby's end to the saga (which never actually ended), it's a nice send-off, and also a harbinger of how often Darkseid would be the Big Bad Wolf in so many DC epics to follow.

In all, this is a terrific collection. It concludes with Kirby-pencilled installments of DC's encyclopedic Who's Who, um, encyclopedia, many of them inked by artists who'd never had a chance to ink Kirby before, including greats Terry Austin and Karl Kesel. Kirby would live for another eight years after the publication of the stories collected here; his stories and characters will probably live on for decades to come. Highly recommended.

The one-and-done stories for DC's mystery and horror comics (and one Western) are enjoyable. Many play with material that would resurface later in Kirby's career, most notably a guest appearance by the Norse god Thor and some Easter-Island aliens who look a lot like the creatures from Saturn in Thor's first appearance at Marvel. Kirby didn't write the dialogue for most of the stories, at least not officially -- DC was also opposed to artists writing their own stories. Weird old 50's DC!

DC was extremely controlling and buttoned-down during the time of Kirby's work collected here. That means a certain amount of reining-in for Kirby, especially in terms of panel composition. Still, there's tons of fascinating stuff here. And the Green Arrow material suggests a science-fictional path for the character that might have lifted him out of years upon years of irrelevance. Cool beans. Recommended.

The Jack Kirby Omnibus Volume 2 (Featuring Super Powers): written and drawn by Jack Kirby and others (1951-1986; collected 2012): This Kirby omnibus collects all of the Jack Kirby stories and story arcs too short to get their own volumes. It spans quite a range. The Black Magic material herein actually comes from the pre-Comics Code 1950's; DC republished the stories they'd acquired from another publisher in the 1970's. And the volume ends with Kirby's last full-length comic book, the final issue of the second Super Powers miniseries, from 1986.

In between are bizarre concepts galore. The 1970's Sandman series would lead pretty much directly to Neil Gaiman's award-winning series of the 1980's. There are one-shots that attempt to cash in on the kung-fu craze (Richard Dragon), the sword-and-sorcery craze (Atlas), revivals of 1940's heroes (Manhunter), revivals of 1940's concepts (the kid-gang comic in The Dingbats of Danger Street), an attempt to focus a DC book on a supervillain rather than a hero (Kobra), and the rare air of a story featuring art from both Kirby and the great Alex Toth.

The lengthy volume (over 600 pages) also features Kirby's last stories of the New Gods, the characters he created when he came to DC in the early 1970's. Darkseid and company appear in the two Super Powers miniseries. In order to get Kirby royalty money for characters created before royalty provisions were attached, some combination of DC executives Paul Levitz, Dick Giordano, and Jenette Kahn had Kirby do minor redesigns on the New Gods characters as part of their inclusion in the new installment in the Super Friends franchise, Super Powers.

Kirby plotted the first miniseries and drew the final issue, with Joey Cavalieri scripting and Adrian Gonzales drawing the first four issues. The second miniseries was written by Paul Kupperberg and pencilled by Kirby. As the Super Powers team was essentially the Justice League, we get Kirby's late-career versions of Superman, Wonder Woman, Dr. Fate, and a host of others. Kirby's failing vision sometimes caused some odd bits of perspective in the 1980's, but overall it's a delight to see him pencilling both his own creations and DC's greatest heroes. His Wonder Woman is convincingly imposing, among other things, and we even get a return to Easter Island, with its alien statues waiting to be reborn.

Greg Theakston does a great job inking this last of Kirby's full-length works, and Kupperberg's scripting is suitably clever and bombastic. Technically (and bizarrely, I guess), this is the last work in Kirby's New Gods saga by Kirby himself. While it's not 'really' Kirby's end to the saga (which never actually ended), it's a nice send-off, and also a harbinger of how often Darkseid would be the Big Bad Wolf in so many DC epics to follow.

In all, this is a terrific collection. It concludes with Kirby-pencilled installments of DC's encyclopedic Who's Who, um, encyclopedia, many of them inked by artists who'd never had a chance to ink Kirby before, including greats Terry Austin and Karl Kesel. Kirby would live for another eight years after the publication of the stories collected here; his stories and characters will probably live on for decades to come. Highly recommended.

Thursday, July 24, 2014

Twins

Cape Fear: adapted by James R. Webb from the novel The Executioners by John D. McDonald; directed by J. Lee Thompson; starring Greogry Peck (Sam Bowden), Robert Mitchum (Max Cady), Polly Bergen (Peggy Bowden), Lori Martin (Nancy Bowden), Martin Balsam (Chief Dutton), and Telly Savalas (Sievers) (1962): This 1962 thriller misses greatness by the gap between the competent direction of J. Lee Thompson and whatever a master like Alfred Hitchcock might have added to the mix. Cape Fear is well worth watching, but one can dream.

The title refers to a river in North Carolina where our protagonist (Gregory Peck) and his family have a cabin and a houseboat. And that's where the movie will climax, after Peck, as prosecuting attorney Sam Bowden, runs through every other gambit he can think of to get ex-convict Robert Mitchum, as Max Cady, to leave him and his family alone. Peck's testimony helped put Cady away years ago for a sexual assault and battery case. Now, Cady wants vengeance.

A strong supporting cast, led by Martin Balsam and Telly Savalas, helps keep things interesting. But it's Robert Mitchum's portrayal of the obsessed and monstrous Cady that makes the movie sing. Here as in the earlier The Night of the Hunter, Mitchum creates a classic movie villain. And he's utterly believeable even in some of the more overheated moments. Slow-moving, almost stately, Mitchum's a full-sized creep-out. He underplays Cady throughout, increasing the menace by decreasing the potential for melodramatic acting excess.

Peck, who produced the film, does that whole Gregory Peck thing in which he's a pillar of decency. A better director might have tightened up some of Peck's reactions to things in a few scenes -- at times Bowden seems a bit slow to react. And a couple of the scenes in which Bowden's or daughter get isolated with Cady around creak and groan with the weight of implausibility. They're saved by the fact that we accept that people whose lives have hitherto been undisturbed by the threat of violence may indeed not take a threat seriously for awhile, regardless of evidence.

The movie simmers and simmers before boiling over in its shadowy, desperate climax. There are other fine setpieces prior to the end (which makes me think of the then-nascent Viet Nam War), especially Cady's pursuit of Bowden's daughter through her school. Cape Fear frames the whole thing as a battle of wits, one in which Cady is surprisingly hypercompetent. He may be a beast, as we're told again and again, but he's a smart one. Recommended.

Cape Fear: adapted by Wesley Strick from the screenplay by James R. Webb that adapted the novel The Executioners by John D. McDonald; directed by Martin Scorsese; starring Robert De Niro (Max Cady), Nick Nolte (Sam Bowden), Jessica Lange (Leigh Bowden), Juliette Lewis (Dannielle Bowden), Joe Don Baker (Claude Kersek), Robert Mitchum (Lieutenant Elgart) and Gregory Peck (Lee Heller) (1991): Somewhere in some alternate universe, there's a remake of Cape Fear directed by Steven Spielberg that stars Harrison Ford as upright attorney Sam Bowden and Bill Murray as obsessive ex-con Max Cady. I'd love to see that movie.

This movie, director Scorsese's first real thriller, isn't quite so interesting. Where the original had Robert Mitchum underplaying as the menacing Cady, this one has Robert De Niro in full-blown cuckoo-banana mode. And eventually Scorsese and the writing join De Niro.

It's still an enjoyable movie. There are some genuine scares and thrills, especially in the first 75 minutes. But then the movie cooks up a lengthy set-piece in the Bowden house that acts as a false climax before taking us to the Cape Fear River, as the original did, for the final showdown. The false climax is excruciating, though not in a good way, and increasingly witless.

By the time a Hitchcock homage rolls around and Nolte starts slipping and sliding in a pool of blood, the thrills have been replaced by unintentional comedy. Five minutes later comes a revelation that caused the entire theatre I saw Cape Fear in when it came out to erupt into jeering laughter. And it is a ridiculous moment.

Scorsese doesn't seem to be invested one whit in making a believeably overwrought thriller, but it's De Niro who's the biggest saboteur of verisimilitude. He's a superhuman blabbermouth. Unlike Mitchum's mostly soft-spoken Cady, De Niro never shuts up, and a lot of his talk is pseudointellectual babble about philosophy and the Bible and great American writers.

Admittedly, it's not so much that he's an expert on Henry Miller or Thomas Wolfe that staggers the imagination -- it's that Bowden's 15-year-old daughter has been assigned Thomas Wolfe's gargantuan Look Homeward, Angel for her summer-school English class. Really? No wonder she's having problems in school. What's the next text assigned, James Joyce's Ulysses?

Because the entire movie exists within a frame narrative, one could argue that the most ridiculous aspects of the movie are embellishments of the narrator. Even then, the movie's sudden loss of conviction is damning.

It's fun to see Scorsese try and fail to make a conventional thriller, however, and the acting by Nick Nolte, Jessica Lange, Juliette Lewis, and Joe Don Baker is fine, though Nolte does seem miscast as Bowden. Indeed, Nolte's acting skill-set really suggests that he should have played Max Cady. That would have been really interesting. Still, by the time De Niro starts speaking in tongues, you really will wish he'd just shut up. Possibly because he sounds an awful lot like Porky Pig. Lightly recommended.

The title refers to a river in North Carolina where our protagonist (Gregory Peck) and his family have a cabin and a houseboat. And that's where the movie will climax, after Peck, as prosecuting attorney Sam Bowden, runs through every other gambit he can think of to get ex-convict Robert Mitchum, as Max Cady, to leave him and his family alone. Peck's testimony helped put Cady away years ago for a sexual assault and battery case. Now, Cady wants vengeance.

A strong supporting cast, led by Martin Balsam and Telly Savalas, helps keep things interesting. But it's Robert Mitchum's portrayal of the obsessed and monstrous Cady that makes the movie sing. Here as in the earlier The Night of the Hunter, Mitchum creates a classic movie villain. And he's utterly believeable even in some of the more overheated moments. Slow-moving, almost stately, Mitchum's a full-sized creep-out. He underplays Cady throughout, increasing the menace by decreasing the potential for melodramatic acting excess.

Peck, who produced the film, does that whole Gregory Peck thing in which he's a pillar of decency. A better director might have tightened up some of Peck's reactions to things in a few scenes -- at times Bowden seems a bit slow to react. And a couple of the scenes in which Bowden's or daughter get isolated with Cady around creak and groan with the weight of implausibility. They're saved by the fact that we accept that people whose lives have hitherto been undisturbed by the threat of violence may indeed not take a threat seriously for awhile, regardless of evidence.

The movie simmers and simmers before boiling over in its shadowy, desperate climax. There are other fine setpieces prior to the end (which makes me think of the then-nascent Viet Nam War), especially Cady's pursuit of Bowden's daughter through her school. Cape Fear frames the whole thing as a battle of wits, one in which Cady is surprisingly hypercompetent. He may be a beast, as we're told again and again, but he's a smart one. Recommended.

Cape Fear: adapted by Wesley Strick from the screenplay by James R. Webb that adapted the novel The Executioners by John D. McDonald; directed by Martin Scorsese; starring Robert De Niro (Max Cady), Nick Nolte (Sam Bowden), Jessica Lange (Leigh Bowden), Juliette Lewis (Dannielle Bowden), Joe Don Baker (Claude Kersek), Robert Mitchum (Lieutenant Elgart) and Gregory Peck (Lee Heller) (1991): Somewhere in some alternate universe, there's a remake of Cape Fear directed by Steven Spielberg that stars Harrison Ford as upright attorney Sam Bowden and Bill Murray as obsessive ex-con Max Cady. I'd love to see that movie.

This movie, director Scorsese's first real thriller, isn't quite so interesting. Where the original had Robert Mitchum underplaying as the menacing Cady, this one has Robert De Niro in full-blown cuckoo-banana mode. And eventually Scorsese and the writing join De Niro.

It's still an enjoyable movie. There are some genuine scares and thrills, especially in the first 75 minutes. But then the movie cooks up a lengthy set-piece in the Bowden house that acts as a false climax before taking us to the Cape Fear River, as the original did, for the final showdown. The false climax is excruciating, though not in a good way, and increasingly witless.

By the time a Hitchcock homage rolls around and Nolte starts slipping and sliding in a pool of blood, the thrills have been replaced by unintentional comedy. Five minutes later comes a revelation that caused the entire theatre I saw Cape Fear in when it came out to erupt into jeering laughter. And it is a ridiculous moment.

Scorsese doesn't seem to be invested one whit in making a believeably overwrought thriller, but it's De Niro who's the biggest saboteur of verisimilitude. He's a superhuman blabbermouth. Unlike Mitchum's mostly soft-spoken Cady, De Niro never shuts up, and a lot of his talk is pseudointellectual babble about philosophy and the Bible and great American writers.

Admittedly, it's not so much that he's an expert on Henry Miller or Thomas Wolfe that staggers the imagination -- it's that Bowden's 15-year-old daughter has been assigned Thomas Wolfe's gargantuan Look Homeward, Angel for her summer-school English class. Really? No wonder she's having problems in school. What's the next text assigned, James Joyce's Ulysses?

Because the entire movie exists within a frame narrative, one could argue that the most ridiculous aspects of the movie are embellishments of the narrator. Even then, the movie's sudden loss of conviction is damning.

It's fun to see Scorsese try and fail to make a conventional thriller, however, and the acting by Nick Nolte, Jessica Lange, Juliette Lewis, and Joe Don Baker is fine, though Nolte does seem miscast as Bowden. Indeed, Nolte's acting skill-set really suggests that he should have played Max Cady. That would have been really interesting. Still, by the time De Niro starts speaking in tongues, you really will wish he'd just shut up. Possibly because he sounds an awful lot like Porky Pig. Lightly recommended.

Wednesday, July 23, 2014

Duets

My Little Chickadee: written by W.C. Fields and Mae West; directed by Edward F. Cline; starring W.C. Fields (Cuthbert J. Twillie), Mae West (Flower Belle Lee), Margaret Hamilton (Mrs. Gideon) and Donald Meek (Amos Budge) (1940): Two of the biggest movie-comedy stars of the 1930's team up for 1940, while hating each other in real life all the while. Both Mae West and W.C. Fields were in the home stretch of movie stardom when they did My Little Chickadee -- West would live for another 40 years but without being a box-office star, while Fields would be dead by 1946.

Their comedy personas are fascinating, though overwhelmed somewhat by time and distance and changing taste. West really isn't all that funny, a problem caused in part by the escalation in movie censorship at the time. It's hard for a comedienne whose comedy is based on double-entendres if the censorship people won't allow them. Fields is a lot funnier. It helps that he does some physical comedy. That stuff never gets old. He falls into a bathtub. He mistakenly romances a goat. Hoo ha!

The two stars wrote their own lines; West also wrote the rest of the movie. Fields was a drunken boor during filming; West was a professional. You can still see the appeal of the then-47-year-old West in her scenes. The movie's certainly an interesting historical artifact, and it does point the way back in time to better individual projects for the two stars. Lightly recommended.

Gravity: written by Alfonso and Jonas Cuaron and George Clooney; directed by Alfonso Cuaron; starring Sandra Bullock (Ryan Stone), George Clooney (Matt Kowalski) and Ed Harris (Mission Control) (2013): The plot and characterization of Gravity creak and groan as if the movie had been penned in the early days of silent movies. The technology needed to make the film amazes, and the film's set-pieces and terse pacing won it a number of Oscars, including Best Director.

I like George Clooney and Sandra Bullock. I'm guessing that much of the movie-viewing public does as well: it's their film. There are almost no other characters. When their space-shuttle mission goes awry, survival in space becomes the movie's point. But because we live in the era of Hollywood Screenwriting 101 and the endless need to supply the viewer with "motivation," Bullock must also be supplied with motivation.

Yes, motivation for surviving in space. Motivation for NOT DYING. Writing in the movies hasn't gotten worse over the years, but it has gotten worse in the blockbusters and big-budget extravaganzas. Sandra Bullock can't just be a professional with a survival instinct. She has to have a sad past. She has to be emotionally crippled until someone gives her a lecture because even imminent death isn't enough to shake her out of her self-pity. Women! Am I right, Hollywood guys?

So some stuff happens in space and Bullock and Clooney have to deal with it. The effects are pretty nice, though occasionally ridiculous to anyone with a modicum of knowledge of physics and orbital mechanics. Stars impossibly twinkle in space. People suddenly become religious. There are pep talks and floating things and microgravity explosions. The title never really makes sense. The actual direction is as old as D.W. Griffith figuring these things out in 1915, and the old tricks still work, especially with CGI and 3-D and astonishingly complicated technical systems. So it goes. Recommended.

Their comedy personas are fascinating, though overwhelmed somewhat by time and distance and changing taste. West really isn't all that funny, a problem caused in part by the escalation in movie censorship at the time. It's hard for a comedienne whose comedy is based on double-entendres if the censorship people won't allow them. Fields is a lot funnier. It helps that he does some physical comedy. That stuff never gets old. He falls into a bathtub. He mistakenly romances a goat. Hoo ha!

The two stars wrote their own lines; West also wrote the rest of the movie. Fields was a drunken boor during filming; West was a professional. You can still see the appeal of the then-47-year-old West in her scenes. The movie's certainly an interesting historical artifact, and it does point the way back in time to better individual projects for the two stars. Lightly recommended.

Gravity: written by Alfonso and Jonas Cuaron and George Clooney; directed by Alfonso Cuaron; starring Sandra Bullock (Ryan Stone), George Clooney (Matt Kowalski) and Ed Harris (Mission Control) (2013): The plot and characterization of Gravity creak and groan as if the movie had been penned in the early days of silent movies. The technology needed to make the film amazes, and the film's set-pieces and terse pacing won it a number of Oscars, including Best Director.

I like George Clooney and Sandra Bullock. I'm guessing that much of the movie-viewing public does as well: it's their film. There are almost no other characters. When their space-shuttle mission goes awry, survival in space becomes the movie's point. But because we live in the era of Hollywood Screenwriting 101 and the endless need to supply the viewer with "motivation," Bullock must also be supplied with motivation.

Yes, motivation for surviving in space. Motivation for NOT DYING. Writing in the movies hasn't gotten worse over the years, but it has gotten worse in the blockbusters and big-budget extravaganzas. Sandra Bullock can't just be a professional with a survival instinct. She has to have a sad past. She has to be emotionally crippled until someone gives her a lecture because even imminent death isn't enough to shake her out of her self-pity. Women! Am I right, Hollywood guys?

So some stuff happens in space and Bullock and Clooney have to deal with it. The effects are pretty nice, though occasionally ridiculous to anyone with a modicum of knowledge of physics and orbital mechanics. Stars impossibly twinkle in space. People suddenly become religious. There are pep talks and floating things and microgravity explosions. The title never really makes sense. The actual direction is as old as D.W. Griffith figuring these things out in 1915, and the old tricks still work, especially with CGI and 3-D and astonishingly complicated technical systems. So it goes. Recommended.

Thursday, July 17, 2014

1985

Lost in America: written by Albert Brooks and Monica McGowan Johnson; directed by Albert Brooks; starring Albert Brooks (David Howard) and Julia Hagerty (Linda Howard) (1985): Brooks takes his often hilariously neurotic persona on the road as David Howard, who transmutes a massive disappointment at work into an attempt to replicate Easy Rider, but in a Winnebago and without the whole death problem at the end.

Lost in America: written by Albert Brooks and Monica McGowan Johnson; directed by Albert Brooks; starring Albert Brooks (David Howard) and Julia Hagerty (Linda Howard) (1985): Brooks takes his often hilariously neurotic persona on the road as David Howard, who transmutes a massive disappointment at work into an attempt to replicate Easy Rider, but in a Winnebago and without the whole death problem at the end.As ad executive Howard, Brooks is his usual self-doubting, blabbermouth self, while Julie Hagerty -- best known for the Airplane movies -- is charming and off-beat as his wife. The movie dissects the ideological fallacies of a certain type of modern personality whose fantasies are dangerous because they're so ill-thought-out and not because they're daring.

Terrific set-pieces abound in Las Vegas, Los Angeles, and on the road. Brooks keeps things moving throughout. There's really no fat on this movie, which clocks in at a satisfying 90 minutes or so. Highly recommended.

Fletch: adapted from the Gregory McDonald novel by Andrew Bergman; directed by Michael Ritchie; starring Chevy Chase (Fletch), Joe Don Baker (Chief Karlin), Dana Wheeler-Nicholson (Gail Stanwyk), Tim Matheson (Alan Stanwyk), George Wendt (Fat Sam), Geena Davis (Larry) and Richard Libertini (Frank) (1985): This enjoyable, occasionally and weirdly aimless mystery-comedy sends investigative reporter Chevy Chase off on the trail of drug-dealers, corrupt police, and a mysterious businessman.

You know it's the mid-1980's because Harold Faltermeyer supplies the music, just as he did on megahit Beverly Hills Cop the year before. Indeed, Faltermeyer replaced the original composer for this movie after the posters had been printed, suggesting that he was parachuted in because studio executives thought he was the reason Beverly Hills Cop grossed a gajillion dollars.

Chase and a very strong cast are very funny throughout, though the fact that Fletch keeps disguising himself for his investigations seems a bit odd given that Chase wasn't one of Saturday Night Live's gifted mimics. It's always nice to see Joe Don Baker, here playing a sinister police chief, with George Wendt, Geena Davis, Richard Libertini, and M. Emmet Walsh also doing solid work in supporting roles.

A relatively complicated plot sputters at times, and Chase really doesn't evoke sympathy when the movie turns to the character's pain over his ex-wife's infidelity. He's just not that type of comic actor. Recommended.

Labels:

albert brooks,

chevy chase,

fletch,

julie hagerty,

lost in america

Wednesday, July 16, 2014

Grimjack Too

Grimjack Omnibus Volume 2: written by John Ostrander; illustrated by Timothy Truman, Tom Sutton, and others (1985-86; this edition 2010): Serialized science fiction and fantasy really had their Golden Age in American comic books in the 1980's, with every publisher (including superhero-centric Marvel and DC) publishing multiple on-going and limited series. Grimjack came from the very science-fictiony First Comics, also then-home to Nexus, Mars, and American Flagg!, among many others. First is long dead, but Grimjack continues to be reprinted and has found new life at other publishers.

This omnibus collects 17 issues of the comic from the 1980's in a thick trade that's slightly smaller in page dimensions than a normal comic book. Grimjack follows the adventures of John Gaunt, the Grimjack of the title, as he battles a variety of threats to both himself and the pan-dimensional metropolis of Cynosure, where all dimensions meet. We do a bit less dimension-hopping in this second omnibus as instead the threats comes to Cynosure.

Gaunt's got the DNA of such conflicted heroes as the Man with No Name and Jonah Hex flowing through his veins. He's a gun for hire who nonetheless finds himself fighting for the common good on more than one occasion, either as a consequence of his employer's problems or as a consequence of his own partially submerged decency. While taking place in Grimjack's 'present,' the issues manage to fill in more of Gaunt's personal history as we go along.

Ostrander's writing is sharp and sympathetic. The science-fictional elements work for the most part, and there are clever riffs on such long-standing tropes as cloning, altered laws of physics, and machine intelligence. Because there are dimensions with wildly different physical laws, magic can also come into play in certain circumstances, though it's often no match for a good blaster in your hand.

Co-creator Timothy Truman's art is lovingly detailed and often unrelentingly grim and bloody, as befits the title character. Truman straddles the border between cartoonist and illustrator, with careful attention to linework and telling detail. His characters remain a bit stiff at times, but the overall effect is striking.

Once Truman leaves the book, Tom Sutton takes over with a slightly looser but no less gritty art job. Sutton does nice work as well, though his 'shattered glass' lay-outs can occasionally be difficult to follow. Overall, a fun piece of hard-boiled, dimension-hopping science fantasy, with enjoyable guest appearances from Nexus's Clonezone the Hilariator and Doug Rice's Dynamo Joe. Recommended.

This omnibus collects 17 issues of the comic from the 1980's in a thick trade that's slightly smaller in page dimensions than a normal comic book. Grimjack follows the adventures of John Gaunt, the Grimjack of the title, as he battles a variety of threats to both himself and the pan-dimensional metropolis of Cynosure, where all dimensions meet. We do a bit less dimension-hopping in this second omnibus as instead the threats comes to Cynosure.

Gaunt's got the DNA of such conflicted heroes as the Man with No Name and Jonah Hex flowing through his veins. He's a gun for hire who nonetheless finds himself fighting for the common good on more than one occasion, either as a consequence of his employer's problems or as a consequence of his own partially submerged decency. While taking place in Grimjack's 'present,' the issues manage to fill in more of Gaunt's personal history as we go along.

Ostrander's writing is sharp and sympathetic. The science-fictional elements work for the most part, and there are clever riffs on such long-standing tropes as cloning, altered laws of physics, and machine intelligence. Because there are dimensions with wildly different physical laws, magic can also come into play in certain circumstances, though it's often no match for a good blaster in your hand.

Co-creator Timothy Truman's art is lovingly detailed and often unrelentingly grim and bloody, as befits the title character. Truman straddles the border between cartoonist and illustrator, with careful attention to linework and telling detail. His characters remain a bit stiff at times, but the overall effect is striking.

Once Truman leaves the book, Tom Sutton takes over with a slightly looser but no less gritty art job. Sutton does nice work as well, though his 'shattered glass' lay-outs can occasionally be difficult to follow. Overall, a fun piece of hard-boiled, dimension-hopping science fantasy, with enjoyable guest appearances from Nexus's Clonezone the Hilariator and Doug Rice's Dynamo Joe. Recommended.

Labels:

cynosure,

dynamo joe,

first comics,

grimjack,

john gaunt,

john ostrander,

nexus,

timothy truman,

tom sutton

Tuesday, July 15, 2014

"A Wicked Voorish Dome in Deep Dendo"

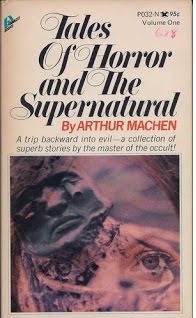

Tales of Horror and the Supernatural Volume 1 by Arthur Machen, containing the following stories: "The Great God Pan", "The Inmost Light", "The Shining Pyramid", "The White People", and "The Great Return" (This edition 1948): Arthur Machen remains one of the ten or so greatest and most influential horror writers who ever lived, more than 100 years since his greatest works were published. Both scientifically inclined and mystical in nature, Machen combined these two traits in stories that expanded upon the philosophical and scientific speculations of Mary Shelley's Frankenstein.

This collection, long out of print, has been supplanted by more complete assemblies of Machen's greatest work. Nonetheless, four of the stories are among the prolific Machen's finest horror stories, while the fifth, the later "The Great Return", shows Machen's later-career move into non-horrifying Catholic mysticism.

"The Great God Pan" and "The White People" are the two titanic stories here. The first concerns a scientific experiment meant to bridge the gap between the material and immaterial world. To do so, the scientist performs a brain operation on a woman. All kinds of Hell result, though it takes decades for the full horror of the experiment to be revealed.

Collapsing the spiritual realm into the physical realm creates a being of sinister potency, and the novella explores not only the nature of evil, but what might be called the evil of nature in certain circumstances: the amoral physical universe is not something to be contemplated without some form of philosophical or ideological buffer between humanity and The Massive. Madness and self-destruction await those who confront the creature born of the experiment: traditionally, those who see the Great God Pan, die.

"The White People", framed by the drawing-room conversation of two men on the nature of true evil, is a stylistic tour-de-force. The main narrative takes the form of a teen-aged girl's journal. Educated from the age of three by a nanny who appears to practice some fairly disturbing witchcraft, the girl moves further and further into the realms of Faery -- the eponymous White People.

The journal works its horrors in a number of subtle ways. The girl's impressions of the disturbing things going on around her are those of a naive innocent, thus leaving certain surmises about what's actually happening to the reader's imagination and deductive abilities. It's brilliantly and sensitively written -- the girl is one of the most heart-breaking narrators in horror fiction by the end of the story -- and the frame narrative, with her story recollected in tranquility, adds an extra layer of verisimilitude and philosophical depth.

Added to these things is a trope that writers such as H.P. Lovecraft would explore more fully -- the story repeatedly refers to rituals and concepts without ever explaining what they truly are. Terms such as 'Aklo' and 'voorish' and 'dhols' would show up in the work of other writers, as would the overall concept of fictional rituals and terms. The great T.E.D. Klein would go so far as to posit "The White People" as a dangerous supernatural text in its own right in his sublime 1984 novel The Ceremonies. There are the White Ceremonies, the Green Ceremonies, and the Scarlet Ceremonies...

Besides the joyful "The Great Return," in which the Holy Grail brings hope to the Welsh during World War One, we also get "The Shining Pyramid," with sinister doings in the countryside and sinister hidden races, and "The Inmost Light," which works as a companion piece to "The Great God Pan." Machen's potent combination of cosmic musings, philosophical enquiry, and mythologies both real and fictional would show the way for many writers to follow. H.P. Lovecraft and his 'disciples' would owe a lot to Machen, and Lovecraft himself praised Machen's work extravagantly in his essay "Supernatural Horror in Literature." He's an indispensable part of the history of horror literature. Because sometimes you really don't want to know what a "wicked voorish dome in Deep Dendo" is, yet you sort of do. Highly recommended.

This collection, long out of print, has been supplanted by more complete assemblies of Machen's greatest work. Nonetheless, four of the stories are among the prolific Machen's finest horror stories, while the fifth, the later "The Great Return", shows Machen's later-career move into non-horrifying Catholic mysticism.

"The Great God Pan" and "The White People" are the two titanic stories here. The first concerns a scientific experiment meant to bridge the gap between the material and immaterial world. To do so, the scientist performs a brain operation on a woman. All kinds of Hell result, though it takes decades for the full horror of the experiment to be revealed.

Collapsing the spiritual realm into the physical realm creates a being of sinister potency, and the novella explores not only the nature of evil, but what might be called the evil of nature in certain circumstances: the amoral physical universe is not something to be contemplated without some form of philosophical or ideological buffer between humanity and The Massive. Madness and self-destruction await those who confront the creature born of the experiment: traditionally, those who see the Great God Pan, die.

"The White People", framed by the drawing-room conversation of two men on the nature of true evil, is a stylistic tour-de-force. The main narrative takes the form of a teen-aged girl's journal. Educated from the age of three by a nanny who appears to practice some fairly disturbing witchcraft, the girl moves further and further into the realms of Faery -- the eponymous White People.

The journal works its horrors in a number of subtle ways. The girl's impressions of the disturbing things going on around her are those of a naive innocent, thus leaving certain surmises about what's actually happening to the reader's imagination and deductive abilities. It's brilliantly and sensitively written -- the girl is one of the most heart-breaking narrators in horror fiction by the end of the story -- and the frame narrative, with her story recollected in tranquility, adds an extra layer of verisimilitude and philosophical depth.

Added to these things is a trope that writers such as H.P. Lovecraft would explore more fully -- the story repeatedly refers to rituals and concepts without ever explaining what they truly are. Terms such as 'Aklo' and 'voorish' and 'dhols' would show up in the work of other writers, as would the overall concept of fictional rituals and terms. The great T.E.D. Klein would go so far as to posit "The White People" as a dangerous supernatural text in its own right in his sublime 1984 novel The Ceremonies. There are the White Ceremonies, the Green Ceremonies, and the Scarlet Ceremonies...

Besides the joyful "The Great Return," in which the Holy Grail brings hope to the Welsh during World War One, we also get "The Shining Pyramid," with sinister doings in the countryside and sinister hidden races, and "The Inmost Light," which works as a companion piece to "The Great God Pan." Machen's potent combination of cosmic musings, philosophical enquiry, and mythologies both real and fictional would show the way for many writers to follow. H.P. Lovecraft and his 'disciples' would owe a lot to Machen, and Lovecraft himself praised Machen's work extravagantly in his essay "Supernatural Horror in Literature." He's an indispensable part of the history of horror literature. Because sometimes you really don't want to know what a "wicked voorish dome in Deep Dendo" is, yet you sort of do. Highly recommended.

Sunday, July 13, 2014

Super Powers!

Simon and Kirby: Superheroes: written and illustrated by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby with additional illustration by Mort Meskin, Gil Kane, and others; Introduction by Neil Gaiman; text pieces by Jim Simon (Original comic-book material 1940-1966; this edition 2010): Before and after there were Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, there were Joe Simon and Jack Kirby. Unlike Lee, Simon could draw, and the two writer-artists also ran a studio for some time in the 1950's. Britain's Titan Books have been doing a fine job of reprinting the work that Simon and Kirby still hold the copyright on, which is to say most of their work for comic-book companies other than Timely/Atlas/Marvel and NPP/DC.

This over-sized, lengthy collection brings together Simon and Kirby's superhero output from the 1940's and 1950's, along with some pages from a brief revival of Fighting American in the mid-1960's. It's both historically compelling and terrifically entertaining.

After a brief stop with a character (the Black Owl) Simon and Kirby didn't create, the volume takes us on a tour of the superhero genre during the time of its great decline. Without the debilitating censorship of the Comics Code Authority in the mid-1950's, it's entirely possible that American superhero comics would have been reduced to a tiny niche of a much larger marketplace with a much broader and more adult-focused comic book audience. Superheroes were already dying off before World War Two ended, and the post-war years only accelerated that decline.

With 1940's and 1950's characters that include Stunt-man and Fighting American, one can see Simon and Kirby striving to move the superhero genre into a different mode of comedy and satire. As Simon notes in his introduction, Fighting American didn't last long, but it did last longer than the proto-Marvel-company's attempt to revive Captain America in the 1950's (the Captain being one of Simon and Kirby's most popular creations).

Both Stunt-man and Fighting American play for the most part as comic takes on superheroes. Fighting American did begin as a serious comic in which the eponymous star-spangled hero fought assorted Communist menaces, but that approach rapidly went from straigghtforward to seriously loopy to intentionally ridiculous. By the time Fighting American and his sidekick Speedboy (!) battle a Communist villain whose superpowers derive from his body odour, we've pretty much left conventional superheroes behind for something a lot more like Mad magazine.

Simon and Kirby's art throughout is a lot of fun. Single- and double-page spreads abound, and there's a pleasing looseness and dynamism to the composition, which generally involved Kirby pencilling and Simon inking. Some of the later Fighting American material is clearly drawn by artists other than Simon and Kirby, but for the most part this is the Real Right Thing.

With the Silver Age underway at DC in the late 1950's, competing companies turned to more straightforward superhero comics again. The Shield and The Fly, both short-lived efforts for the Archie Comics superhero wing, remain satire-free while nonetheless continuing with an out-sized loopiness that's pure Silver Age.

The Shield, yet another star-spangled hero, has powers more like Superman's than Captain America's. The Fly's origin is completely nuts. Benevolent aliens who look like flies (and indeed sometimes are flies) invest the title character with the power of the Fly in order to fight evil. None of this involves eating crap, much less possessing a penis several times longer than his own body. Well, there was a Comics Code.

Other stories include the use of 3-D glasses (in Captain 3-D, natch) and an experiment with an anomalous three-person crime-fighting team. Uncompleted stories, unused covers, and some solid historical essays from Jim Simon round out the volume. It's an outstanding piece of entertainment and scholarship, with remastered art that often looks much better than what the big boys at Marvel and DC have managed with their reprints. Highly recommended.

This over-sized, lengthy collection brings together Simon and Kirby's superhero output from the 1940's and 1950's, along with some pages from a brief revival of Fighting American in the mid-1960's. It's both historically compelling and terrifically entertaining.

After a brief stop with a character (the Black Owl) Simon and Kirby didn't create, the volume takes us on a tour of the superhero genre during the time of its great decline. Without the debilitating censorship of the Comics Code Authority in the mid-1950's, it's entirely possible that American superhero comics would have been reduced to a tiny niche of a much larger marketplace with a much broader and more adult-focused comic book audience. Superheroes were already dying off before World War Two ended, and the post-war years only accelerated that decline.

With 1940's and 1950's characters that include Stunt-man and Fighting American, one can see Simon and Kirby striving to move the superhero genre into a different mode of comedy and satire. As Simon notes in his introduction, Fighting American didn't last long, but it did last longer than the proto-Marvel-company's attempt to revive Captain America in the 1950's (the Captain being one of Simon and Kirby's most popular creations).

Both Stunt-man and Fighting American play for the most part as comic takes on superheroes. Fighting American did begin as a serious comic in which the eponymous star-spangled hero fought assorted Communist menaces, but that approach rapidly went from straigghtforward to seriously loopy to intentionally ridiculous. By the time Fighting American and his sidekick Speedboy (!) battle a Communist villain whose superpowers derive from his body odour, we've pretty much left conventional superheroes behind for something a lot more like Mad magazine.

Simon and Kirby's art throughout is a lot of fun. Single- and double-page spreads abound, and there's a pleasing looseness and dynamism to the composition, which generally involved Kirby pencilling and Simon inking. Some of the later Fighting American material is clearly drawn by artists other than Simon and Kirby, but for the most part this is the Real Right Thing.

With the Silver Age underway at DC in the late 1950's, competing companies turned to more straightforward superhero comics again. The Shield and The Fly, both short-lived efforts for the Archie Comics superhero wing, remain satire-free while nonetheless continuing with an out-sized loopiness that's pure Silver Age.

The Shield, yet another star-spangled hero, has powers more like Superman's than Captain America's. The Fly's origin is completely nuts. Benevolent aliens who look like flies (and indeed sometimes are flies) invest the title character with the power of the Fly in order to fight evil. None of this involves eating crap, much less possessing a penis several times longer than his own body. Well, there was a Comics Code.

Other stories include the use of 3-D glasses (in Captain 3-D, natch) and an experiment with an anomalous three-person crime-fighting team. Uncompleted stories, unused covers, and some solid historical essays from Jim Simon round out the volume. It's an outstanding piece of entertainment and scholarship, with remastered art that often looks much better than what the big boys at Marvel and DC have managed with their reprints. Highly recommended.

Labels:

captain 3-d,

captain america,

fighting american,

jack kirby,

joe simon,

speedboy,

stan lee,

stunt-man,

the fly,

the shield

Saturday, July 12, 2014

Scary Antiquary

Canon Alberic's Scrap-book and other stories by M.R. James, containing the following stories: "Canon Alberic's Scrap-book", "The Rose Garden", "The Mezzotint", and "The Stalls of Barchester Cathedral" (This edition 2010): Nice little entry in Penguin's 50th anniversary Modern Classics series collects four of early 20th-century ghost-story master M.R. James' ghost stories.

James continues to resist becoming dated, and his ghost stories remain a model of economy and terror at their best. Three of the stories here are major, while "The Rose Garden" is a curious inclusion. It's not bad, it's simply not among his best, as it comes to an oddly sputtering end after a terrific start. It is emblematic of one of James' fictional concerns, however -- the dangers that a lack of specific knowledge can bring when one starts mucking about.

Of the other three, "Canon Alberic's Scrap-book" is the scariest, and is one of the finest examples of James' technique of gradually introducing a supernatural menace. It's also the most antiquarian of the stories included here (James titled his first collection Ghost Stories of an Antiquary). The protagonist encounters Something Awful as a direct result of his interest in an old, small-town French church.

"The Mezzotint" and "The Stalls of Barchester Cathedral" follow similar paths into the past, with an old Mezzotint and old journals, respectively. "The Mezzotint" offers horror at one remove, as the protagonist views the past through the eponymous object in far more detail than is usual for a mezzotint.

"The Stalls of Barchester Cathedral" wouldn't be out of place in a revenge-oriented horror comic book of the 1950's. While it involves a supernatural event of the distant past pieced together by a contemporary protagonist from a box of papers and letters, the story still manages some of James' most effective creep-out moments. As we learn in ghost story after ghost story, if you don't know who's at the door, don't invite them in. Highly recommended.

James continues to resist becoming dated, and his ghost stories remain a model of economy and terror at their best. Three of the stories here are major, while "The Rose Garden" is a curious inclusion. It's not bad, it's simply not among his best, as it comes to an oddly sputtering end after a terrific start. It is emblematic of one of James' fictional concerns, however -- the dangers that a lack of specific knowledge can bring when one starts mucking about.

Of the other three, "Canon Alberic's Scrap-book" is the scariest, and is one of the finest examples of James' technique of gradually introducing a supernatural menace. It's also the most antiquarian of the stories included here (James titled his first collection Ghost Stories of an Antiquary). The protagonist encounters Something Awful as a direct result of his interest in an old, small-town French church.

"The Mezzotint" and "The Stalls of Barchester Cathedral" follow similar paths into the past, with an old Mezzotint and old journals, respectively. "The Mezzotint" offers horror at one remove, as the protagonist views the past through the eponymous object in far more detail than is usual for a mezzotint.

"The Stalls of Barchester Cathedral" wouldn't be out of place in a revenge-oriented horror comic book of the 1950's. While it involves a supernatural event of the distant past pieced together by a contemporary protagonist from a box of papers and letters, the story still manages some of James' most effective creep-out moments. As we learn in ghost story after ghost story, if you don't know who's at the door, don't invite them in. Highly recommended.

Friday, July 11, 2014

Fat Birds

In a World...: written and directed by Lake Bell; starring Lake Bell (Carol), Rob Corddry (Moe), Alexandra Holden (Jamie), Ken Marino (Gustav), Demetri Martin (Louis), Fred Melamed (Sam), and Michaela Watkins (Dani) (2013): Lake Bell does triple duty on this Hollywood-centric comedy. And in her feature-film writing-and-directing debut, she really brings it.

Many of the delights of this film come from surprise, so I'll just note that it's primarily about Hollywood voiceover artists. You know, the voices you hear on movie ads, movie trailers, and in TV commercials. And it's a real delight, a light-hearted industry satire that tackles feminist issues with intelligence and wit.

Bell is terrific as the protagonist, whose father is a great and hilariously self-important voiceover artist and who herself aspires to become the first great female voiceover artist. The supporting roles are all warmly written, with Rob Corddry getting his best film role ever as Bell's brother-in-law. All this, and a weirdly plausible Young Adult movie named The Amazon Games, clips of which we see. Highly recommended.

Saving Mr. Banks: written by Kelly Marcel and Sue Smith; directed by John Lee Hancock; starring Emma Thompson (P.L. Travers), Tom Hanks (Walt Disney), Annie Rose Buckley (Ginty), Colin Farrell (Ginty's Father), Paul Giamatti (Ralph), Bradley Whitford (Don DaGradi), B.J. Novak (Robert Sherman) and Jason Schwartzman (Richard Sherman) (2013): The often hilariously fractious relationship between Mary Poppins creator P.L. Travers and Walt Disney, who's been trying to make a movie of Travers' novel since the 1940's, makes for a pretty funny movie.

Of course, we also have the non-hilarious stuff detailing Travers' childhood relationship with her troubled, alcoholic father in the Australian outback. The movie threads together this formative storyline with one involving Travers' two-week stay in Hollywood as she worked with Disney writers while debating whether or not to sign over the rights to Mary Poppins to Disney.

The cast is excellent from top to bottom. Hanks probably deserved more recognition for his work as Disney, and Thompson is typically excellent as the prickly Travers. Colin Farrell is unusually sweet as Travers' father. B.J. Novak and Jason Schwartzman play the songwriting Sherman brothers with understated humour. Paul Giamatti is particularly charming in what could have been a thanklessly sentimental role as the driver assigned to get Travers to and from her Beverly Hills hotel each day.

The movie plays fast and loose with certain facts of the movie's development, but much of the film's Hollywood portion really did happen. Really, the funniest thing the movie doesn't address is Dick Van Dyke's terrible attempt at a Cockney accent in the movie of Mary Poppins. There is a reason Travers didn't want him as Bert -- even Van Dyke thought he was wrong for the part! Recommended.

Many of the delights of this film come from surprise, so I'll just note that it's primarily about Hollywood voiceover artists. You know, the voices you hear on movie ads, movie trailers, and in TV commercials. And it's a real delight, a light-hearted industry satire that tackles feminist issues with intelligence and wit.

Bell is terrific as the protagonist, whose father is a great and hilariously self-important voiceover artist and who herself aspires to become the first great female voiceover artist. The supporting roles are all warmly written, with Rob Corddry getting his best film role ever as Bell's brother-in-law. All this, and a weirdly plausible Young Adult movie named The Amazon Games, clips of which we see. Highly recommended.

Saving Mr. Banks: written by Kelly Marcel and Sue Smith; directed by John Lee Hancock; starring Emma Thompson (P.L. Travers), Tom Hanks (Walt Disney), Annie Rose Buckley (Ginty), Colin Farrell (Ginty's Father), Paul Giamatti (Ralph), Bradley Whitford (Don DaGradi), B.J. Novak (Robert Sherman) and Jason Schwartzman (Richard Sherman) (2013): The often hilariously fractious relationship between Mary Poppins creator P.L. Travers and Walt Disney, who's been trying to make a movie of Travers' novel since the 1940's, makes for a pretty funny movie.

Of course, we also have the non-hilarious stuff detailing Travers' childhood relationship with her troubled, alcoholic father in the Australian outback. The movie threads together this formative storyline with one involving Travers' two-week stay in Hollywood as she worked with Disney writers while debating whether or not to sign over the rights to Mary Poppins to Disney.

The cast is excellent from top to bottom. Hanks probably deserved more recognition for his work as Disney, and Thompson is typically excellent as the prickly Travers. Colin Farrell is unusually sweet as Travers' father. B.J. Novak and Jason Schwartzman play the songwriting Sherman brothers with understated humour. Paul Giamatti is particularly charming in what could have been a thanklessly sentimental role as the driver assigned to get Travers to and from her Beverly Hills hotel each day.

The movie plays fast and loose with certain facts of the movie's development, but much of the film's Hollywood portion really did happen. Really, the funniest thing the movie doesn't address is Dick Van Dyke's terrible attempt at a Cockney accent in the movie of Mary Poppins. There is a reason Travers didn't want him as Bert -- even Van Dyke thought he was wrong for the part! Recommended.

Wednesday, July 9, 2014

Ghoulish Grab-bag

Nameless Places: edited by Gerald W. Page, containing the following stories: Glimpses by A. A. Attanasio; The Night of the Unicorn by Thomas Burnett Swann; The Warlord of Kul Satu by Brian N. Ball; More Things by G. N. Gabbard; The Real Road to the Church by Robert Aickman; The Gods of Earth by Gary Myers; Walls of Yellow Clay by Robert E. Gilbert; Businessman's Lament by Scott Edelstein; Dark Vintage by Joseph F. Pumilia; Simaitha by David A. English; In the Land of Angra Mainyu by Stephen Goldin; Worldsong by Gerald W. Page; What Dark God? by Brian Lumley; The Stuff of Heroes by Bob Maurus; Forringer's Fortune by Joseph Payne Brennan; Before the Event by Denys Val Baker; In 'Ygiroth by Walter C. DeBill, Jr.; The Last Hand by Ramsey Campbell; Out of the Ages by Lin Carter; Awakening by David Drake; In the Vale of Pnath by Lin Carter; Chameleon Town by Carl Jacobi; Botch by Scott Edelstein; Black Iron by David Drake; Selene by E. Hoffmann Price; The Christmas Present by Ramsey Campbell; and Lifeguard by Arthur Byron Cover (1975).

Some of this classic (and never-reprinted) Arkham House anthology from the demon-haunted 1970's consists of stories submitted to Arkham co-founder August Derleth before his death in 1971. Overall, there's no real theme to the anthology, as editor Gerald Page notes in his introduction. It's simply a large collection of often very-short stories of horror, dark fantasy, and the supernatural.

This being an Arkham House release, and Arkham having been originally founded to get the stories of H.P. Lovecraft into permanent hardcover editions, there's more than a soupcon of Lovecraftian shenanigans at work here. Lin Carter and a few others pastiche for all they're worth, both Cthulhu Mythos-era HPL and earlier Dunsanian HPL. Joseph Payne Brennan refers to Lovecraft in his story, though the style and content of "Forringer's Fortune" remain much in line with Brennan's other work, written in a much more demotic plain style than anything Lovecraft assayed.

It's interesting to me that two horror writers who began as Lovecraft pastiche writers, Brian Lumley and Ramsey Campbell, both give us tales of non-Lovecraftian supernatural horror set on trains. Both tales are effective, though Campbell's "The Last Hand" is the more effective simply because he doesn't try to explain outright the true identities of the three passengers his protagonist must engage in a poker game with.